The Five Litre Rule: Horror, Blood and Bluebeard’s Castle

Inside of her new husband’s windowless home, Judith notes that the walls are wet. They are covered in blood, and though she doesn’t know it yet, so is everything else in this house that will soon become her tomb. She is the latest bride of Bluebeard, the man with a sanguine Midas touch, the legendary killer of women.

Part of a double bill playing at the Canadian Opera Company throughout May, Bluebeard’s Castle, by Béla Bartók, is filled with blood. The entirety of the opera involves the newlywed Judith convincing her withdrawn and tormented husband to open seven locked doors in his dark castle. Behind each threshold she finds a grotesque amount of human bodily fluid and only once, when she discovers a lake made of white tears, is it not blood.

The COC’s double bill of Bluebeard’s Castle and the equally horrific Erwartung is directed by Canadian theatre visionary Robert Lepage, who manages to take these two operas and breathe into them a contemporary sense of abject horror. With Erwartung he does this with the application of mind bending acrobatics that help illustrate the protagonist’s mental anguish, but with Bluebeard’s Castle, a much more straightforward and popularly known piece of expressionism, Lepage achieves high terror with the oldest trick in the book: drowning everything in people juice.

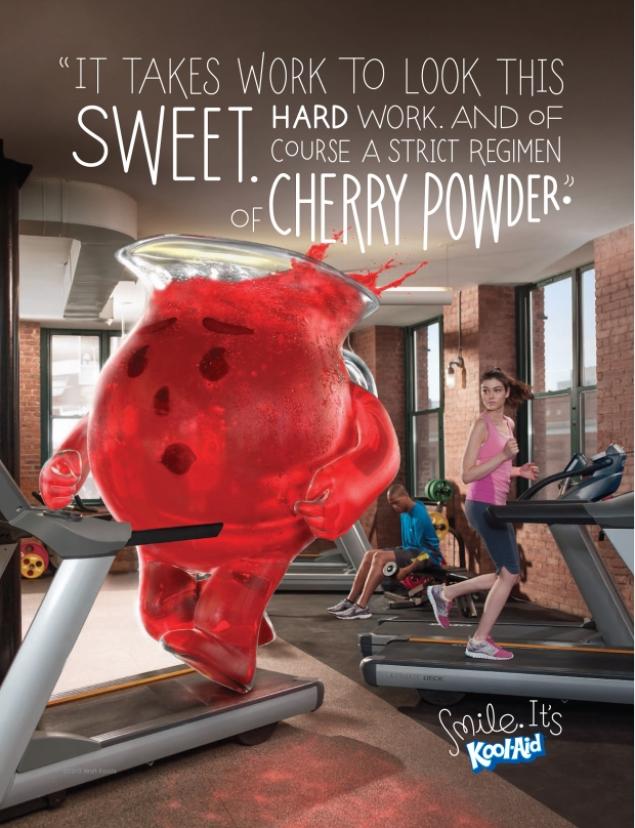

Oh man... Nothing gets people juice out. (image via coc.ca)

The horror of blood is the horror of the unknown in the face of terrible possibility. Blood carries with it an implication of identity, since it is something each of us intimately houses within our bodies and if it were to be taken from us we would cease to exist. Outside of a body, we know that blood once belonged to someone (or at least something) but we lose our capacity to label it.

Blood is not always scary. In Bluebeard’s Castle it actually becomes kind of funny when viewed from a modern paradigm of repetition comedy. Behind the fourth door, where Judith finds her demented husband’s garden, the reveal that it’s all covered in blood is expected, so to deliver on that audience anticipation without any variation or self-reflexive acknowledgement is to enter into absurd territory. It's Family Guy by way of Béla Bartók.

Judith's constant discovery of blood is a reminder that human plasma is commonplace and not, in and of itself, horrific. Blood gives us life, and to donate it to other people in need is considered a highly moral deed. In many forms of Christianity, drinking the blood of Jesus is considered one of the most Holy acts a follower can perform and she is invited to on a weekly basis.

When you are cut, the sight of blood can induce panic, but it shouldn't induce terror. We know that it flows through us, and we should actually more scared, on a personal level, of the absence of our blood, than its presence, a useful rule of thumb being that if you can see your own gore, you’re still alive.

The typical adult human carries in them about five litres of blood. That’s enough plasma and red blood cells to fill two and a half large bottles of ginger ale (or whatever soda you prefer to ruin while reading this). Imagine those pop bottles: they have no face, or hopes, or dreams; they don’t have jobs, or put on soft clothes before they go to sleep. And yet, the contents of those plastic soft drink containers evoke the absence of those listed human qualities. Five litres of blood used to have all of that and more when it was in some veins and delivering oxygen to vital organs, but when extracted and pooled or used to paint your castle’s interior, it is a complex material stripped of purpose and value (though not necessarily stripped of its infectious agents).

If it makes you feel more comfortable, feel free to imagine 5L of cherry Kool-Aid instead of blood. Yum!

In great abundance things become even more upsetting. If five litres of blood is all one person can hold, then a river of blood, an elevator full of blood or, in the case of Bluebeard, a castle covered in blood, requires that we further dilute the idea of the individual from whom it inevitably first squirted. Two and a half pop bottles can hold the blood of a single human, but what if you encountered three pop bottles filled to the top with blood? There is at least a bit of an additional person in there, but at that point the unholy refreshments could be provided by any number of suppliers. When it's inside of us, it’s just us, but when blood is free flowing and from multiple donors it mixes and becomes un-extractable. It's like mixing Pepsi and Coke, but for Draculas.

Too see blood in abundance of five litres is to behold a truly upsetting reality. Our precious identity can be taken from us, and we can be transformed from people into fluids. In the Outlook Hotel of your nightmares, when the elevator doors open up, the question isn’t how you’re going to get the stains out of your cool Apollo 11 sweater, the question is: who were these people that I’m wading through? A puddle of blood is an object with a hidden identity. A river of blood is a population transformed into a climatological phenomenon.

I hate riding packed elevators.

In Lepage’s Bluebeard’s Castle, when Judith opens the final door, expecting to find the corpses of her husband’s previous three wives, the (surprisingly) still living women emerge from the stage floor covered in an abundance of blood. I can't say I have ever seen something so truly horrific on stage. Doused in visceral fluid, they carry on them transformed human existence. Lives have gone into their wardrobe (including their own) and you will never know the amount of death, dreams and simple pleasures that contributed to their sticky, salty, possibly infectious liquid accessories.

The maniac Bluebeard ends the opera with an apocalyptic note. Now that he’s claimed his final victim there will be eternal darkness, he sings. The line is spine chilling in the context of the opera’s climax, and Béla Bartók’s music brings the show to an appropriately unsettling end, but nothing evokes horror like the thought of her precious, life giving and unique blood joining the anonymous red fluid that coats the walls of a castle no living eyes have seen save its owner’s.