The Alien Landscape of Dreams: Scriptwelder's Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep

"It was all just a dream."

Raise your hand if that line, or a slight variation thereof, sends you into paroxysms of rage. In modern media, this is one of those unforgivable clichés, a flimsy explanation for events told in a fictional narrative that has been so thoroughly trod over that it could be repurposed as a doormat. There was time when it was charming, even fresh, but that time is roughly about the same period when Dorothy and Toto were traipsing around Oz. So if you want to set your work in a dream, you'd better bloody well have a good reason, or at the very least be bringing something fresh to the table.

Scriptwelder, thankfully, does, in his series Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep.

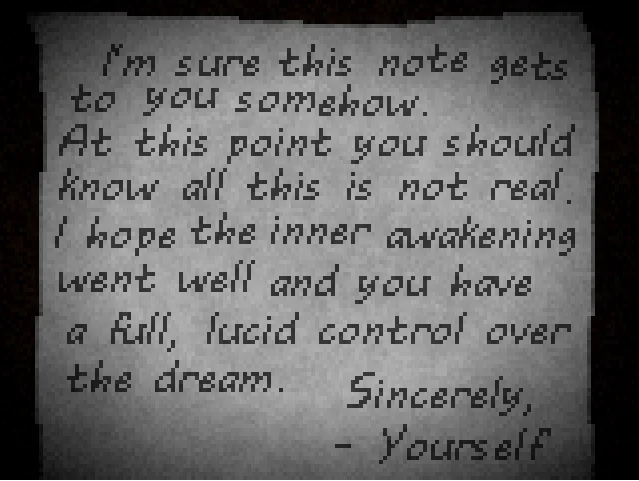

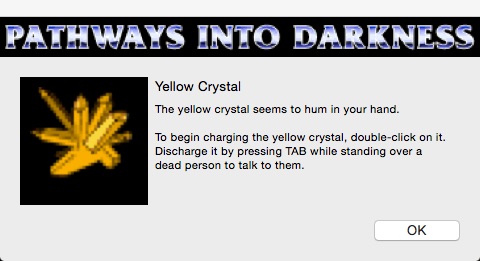

Yes, the title(s) is a bit of a lead brick, but what sets this little series apart from other "dream exploration" horror games I've played is the upfront acknowledgement that you are dreaming. More to the point, you are dreaming deliberately. You play an unnamed person who is fascinated by the concept of lucid dreaming, and is convinced that tapping into this space of imagination and self-awareness holds some strange power and may, in fact, be interacting on some level with reality.

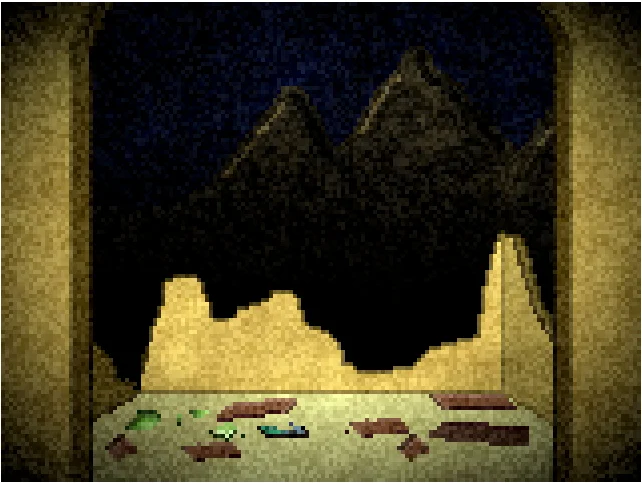

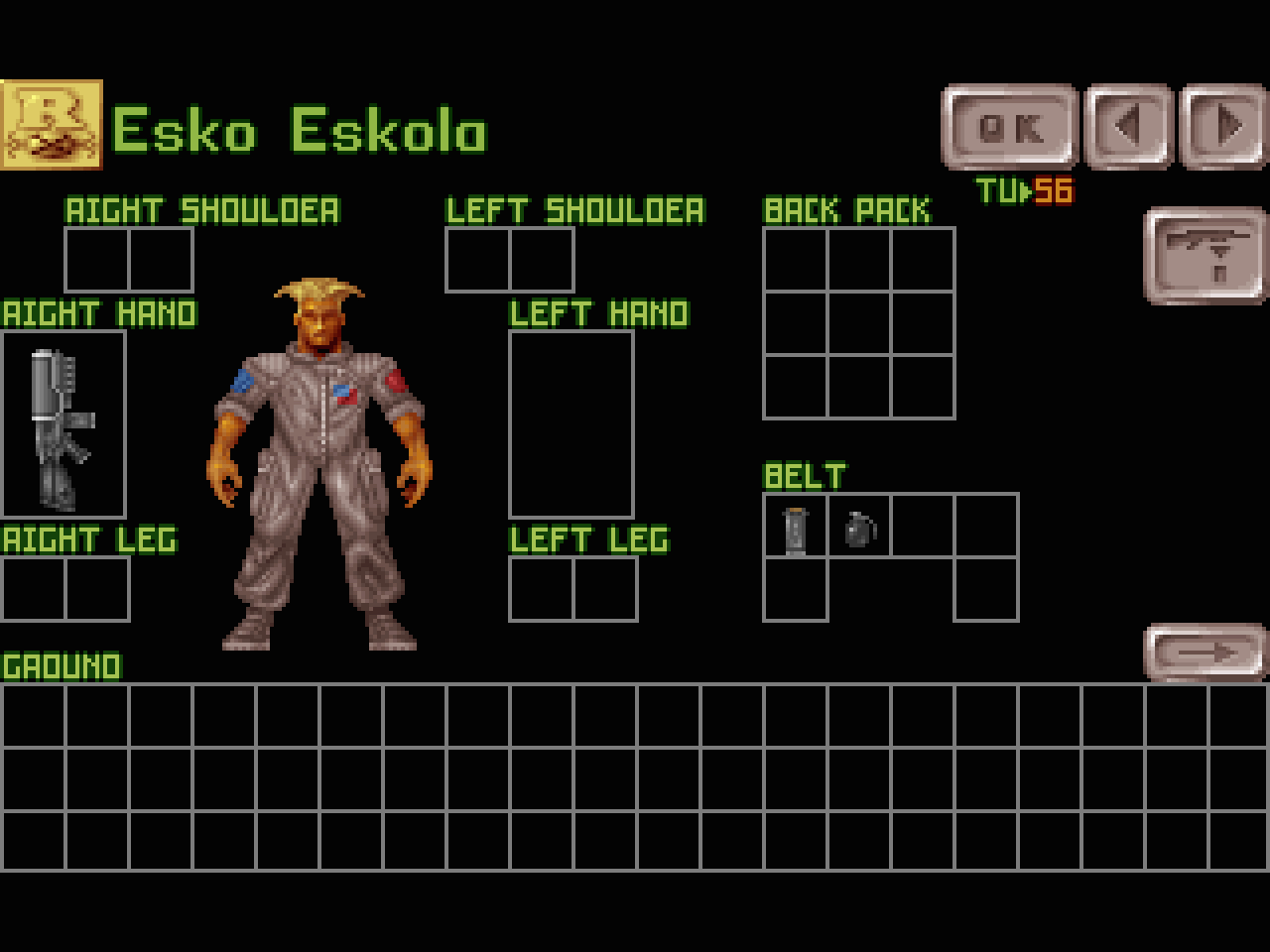

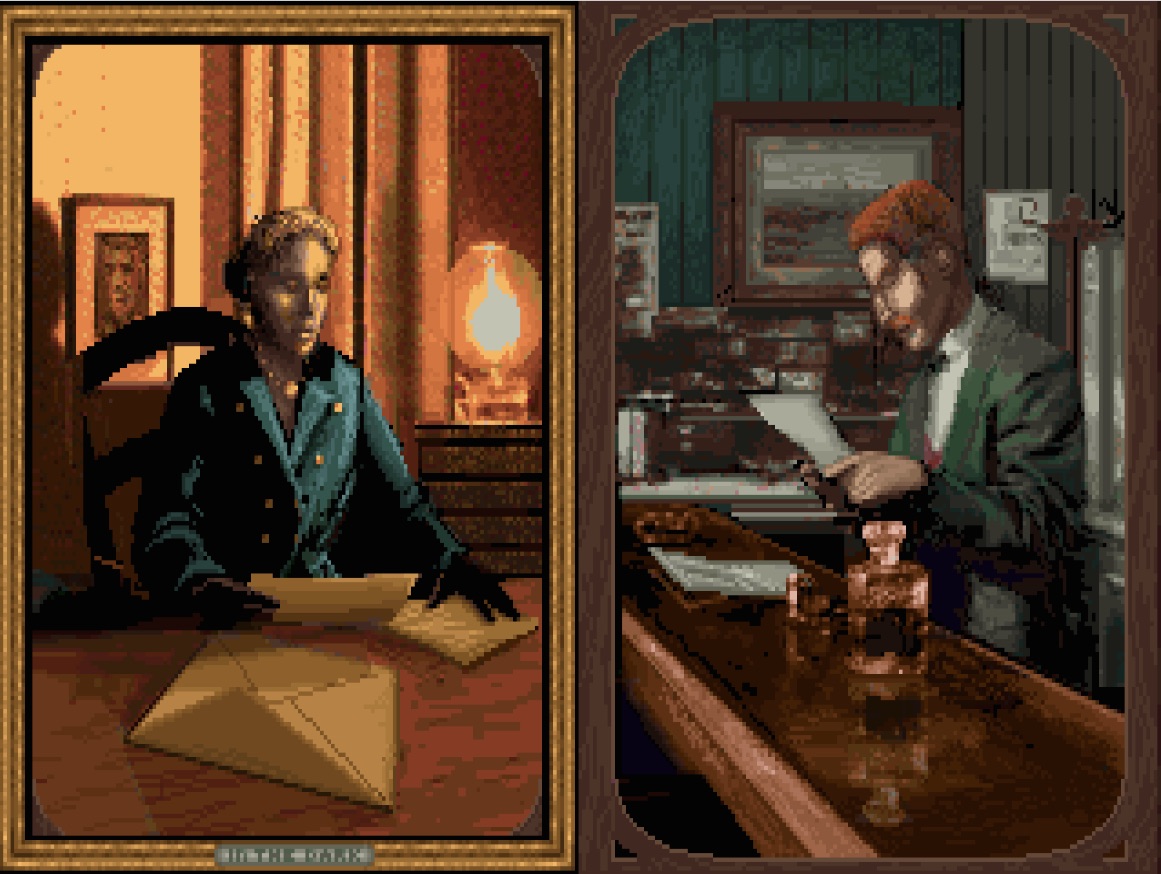

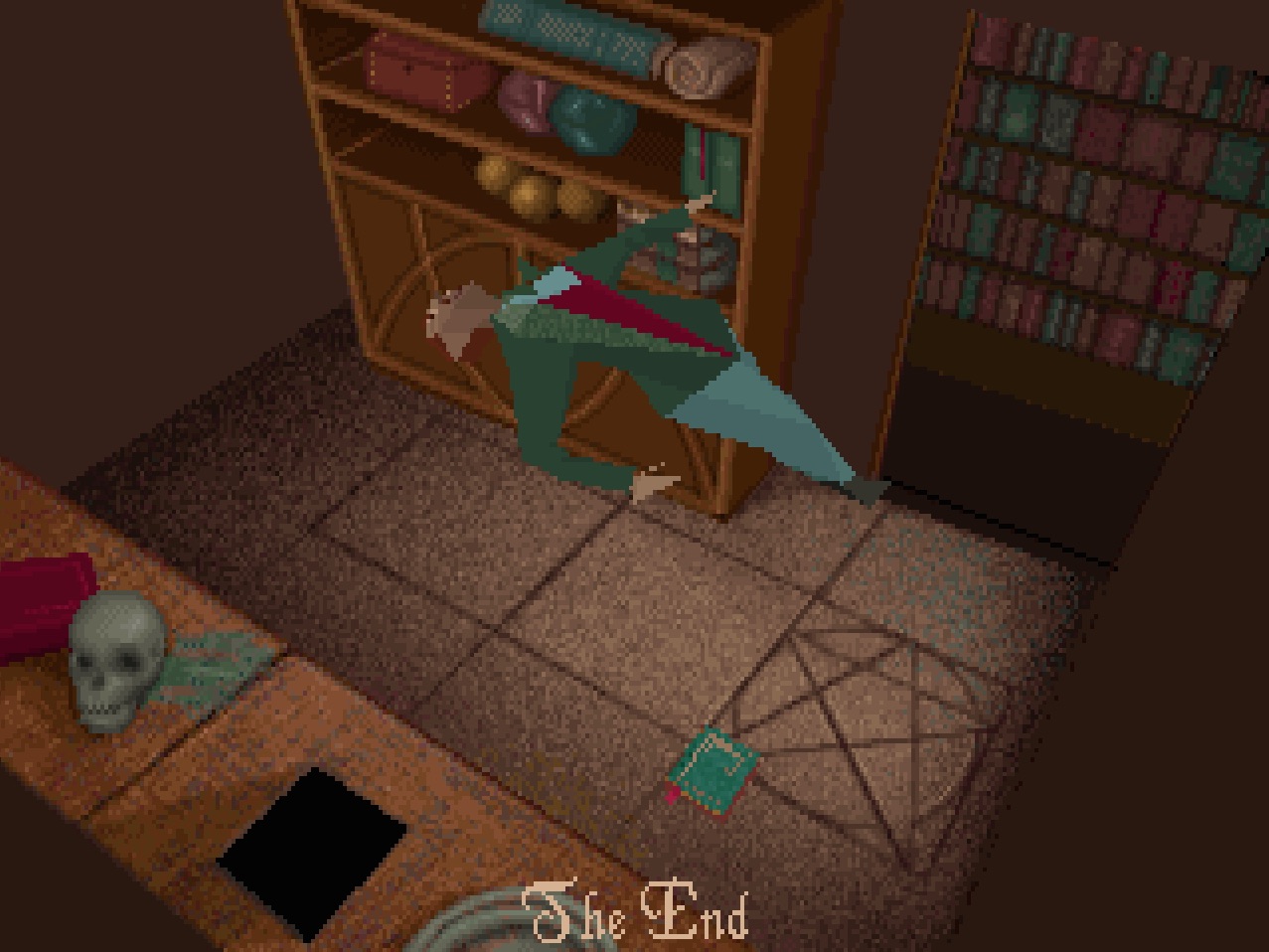

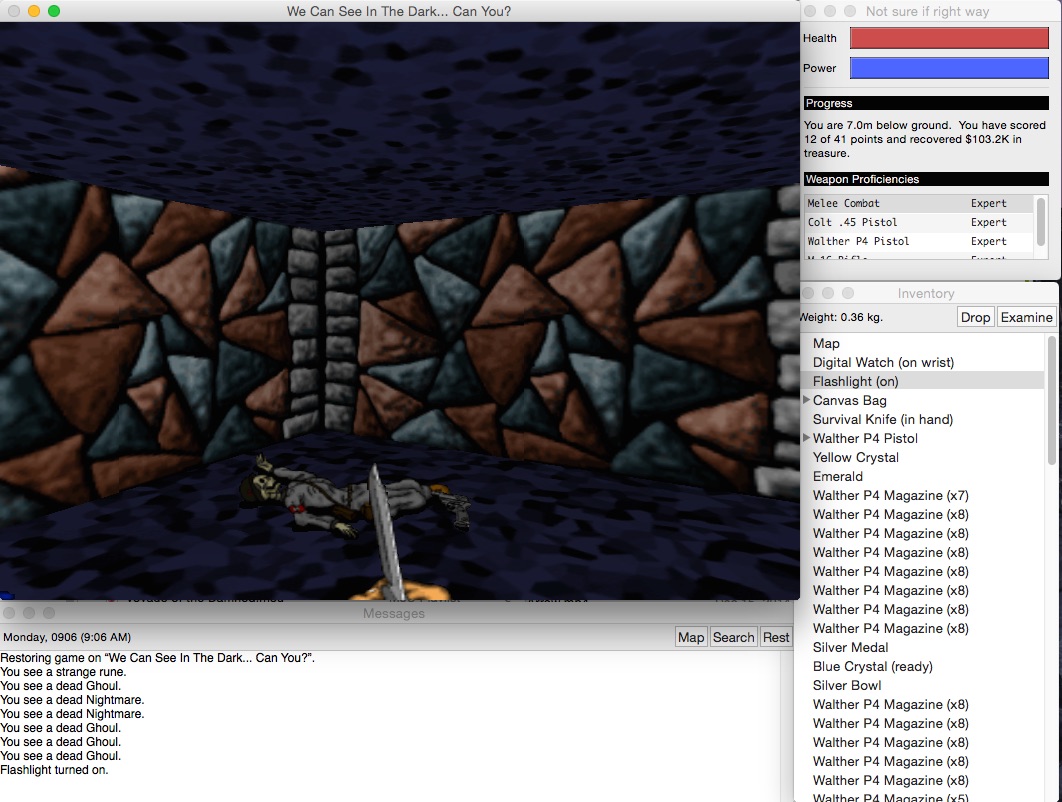

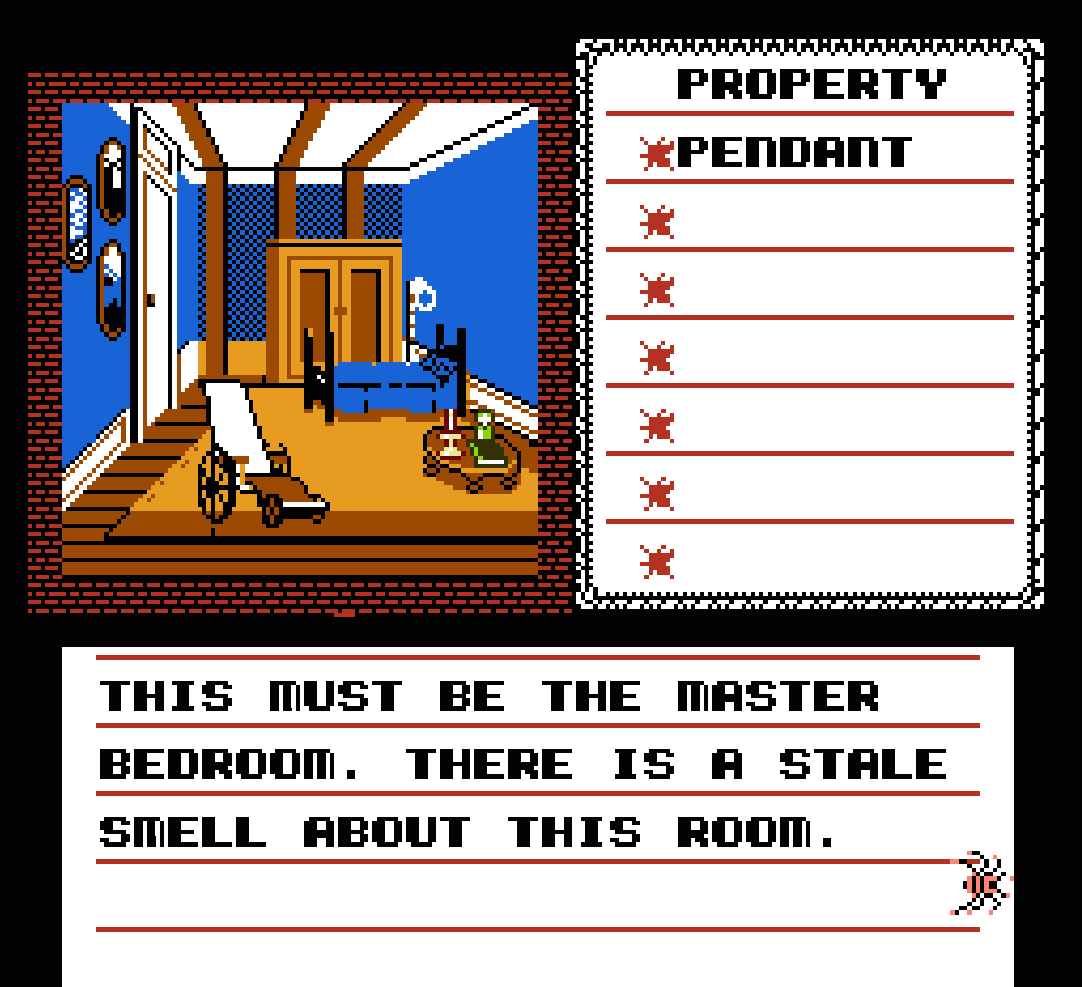

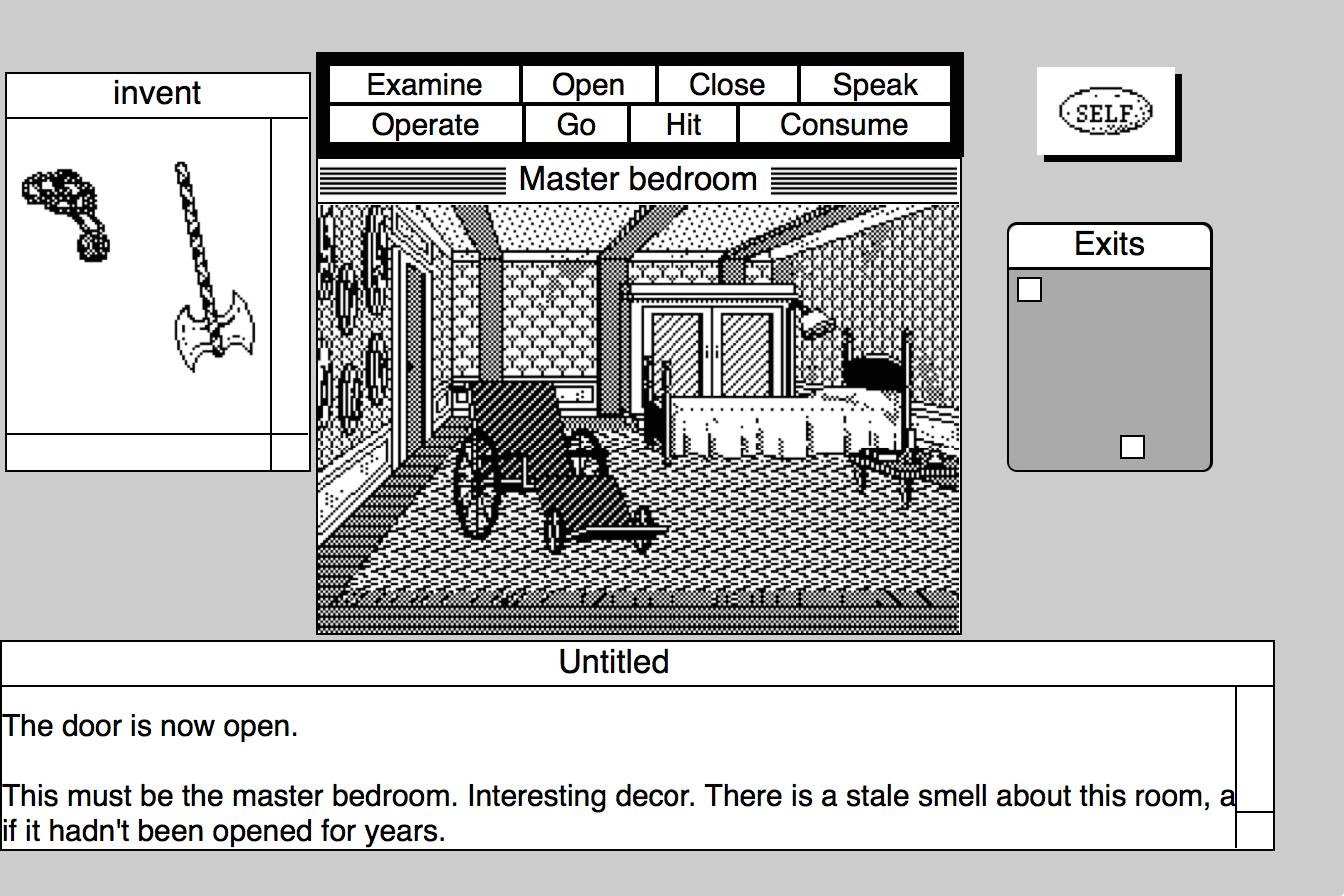

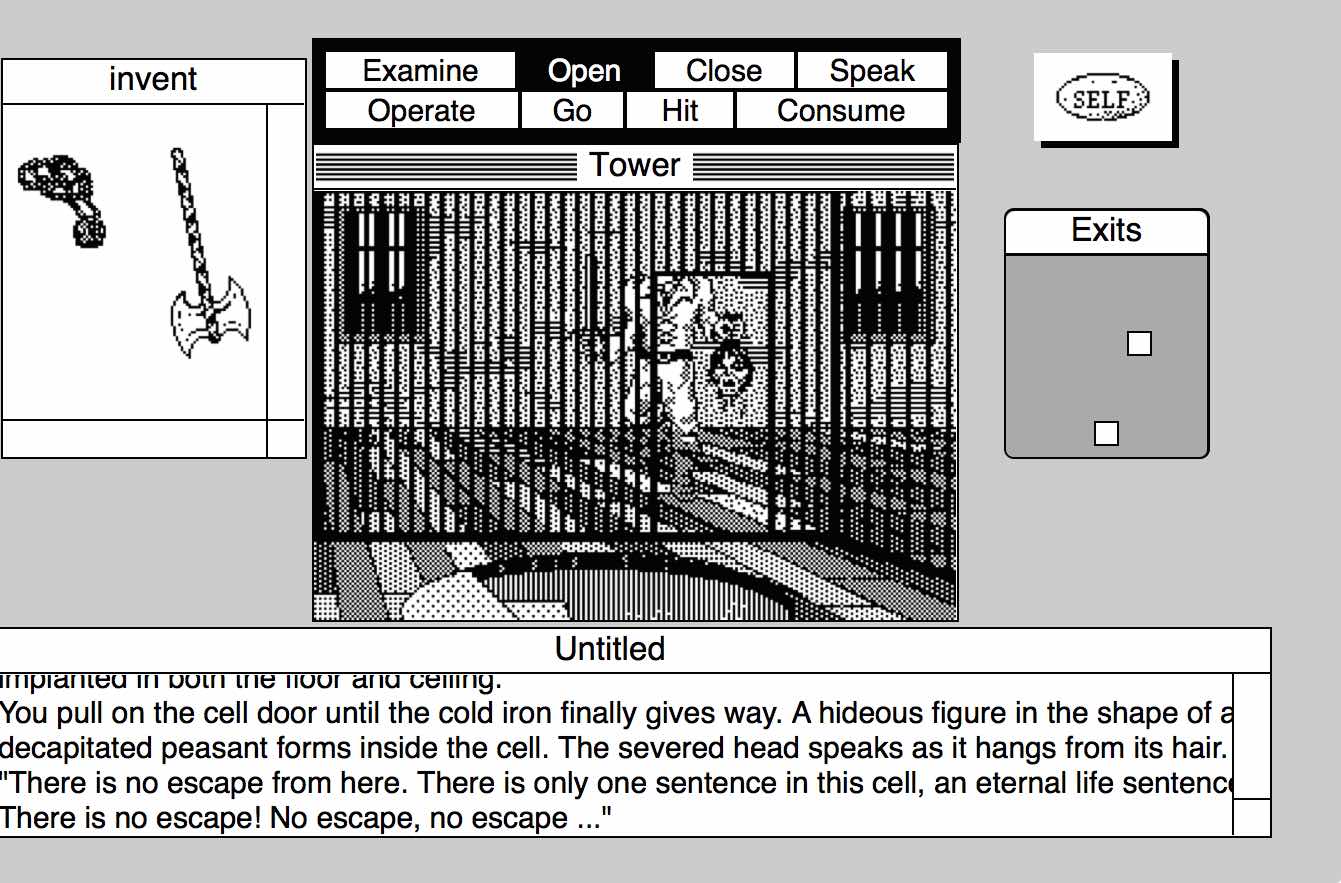

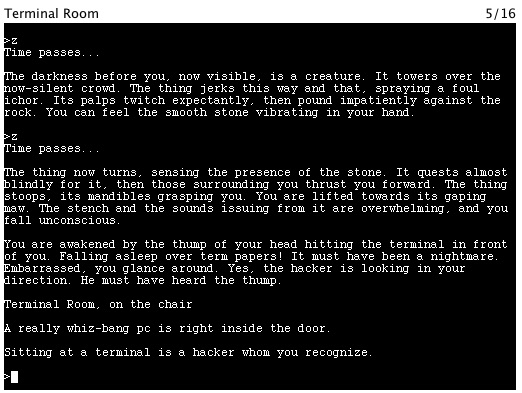

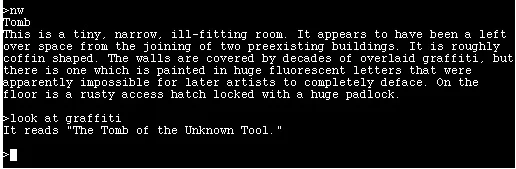

The games are all point and click adventure games, which hold a special fondness in my heart, and feature the same style of graphics as The Last Door, all pixelly goodness. The main difference, however, is that the third-person perspective of that series is replaced here with a first-person view more akin to Uninvited.

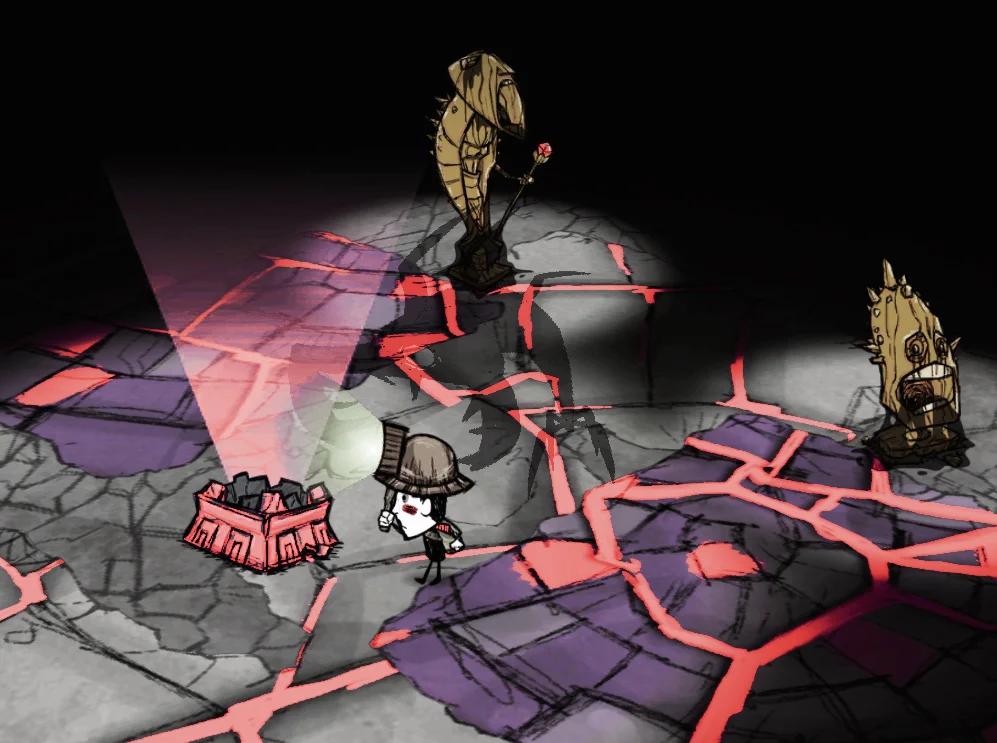

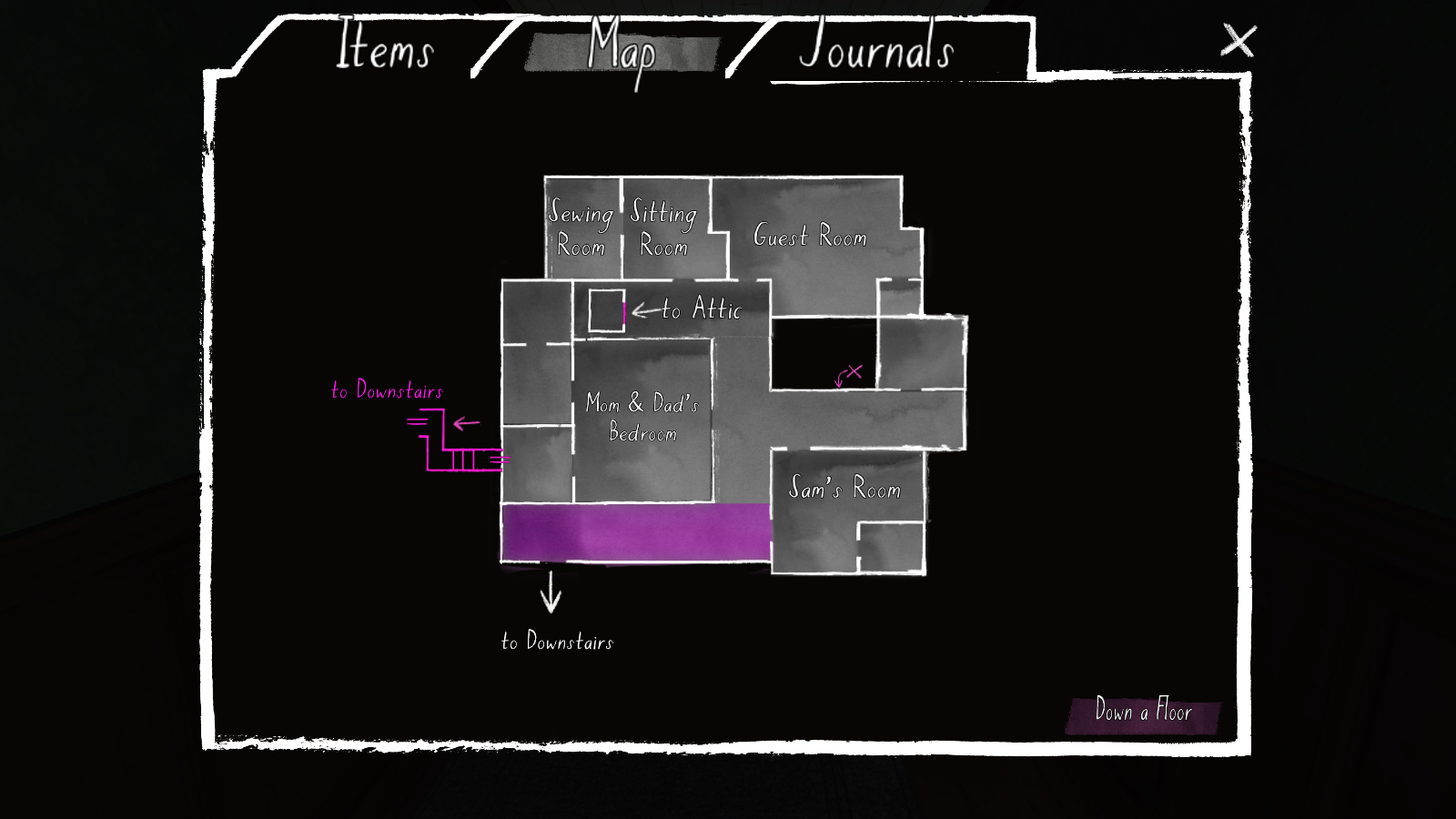

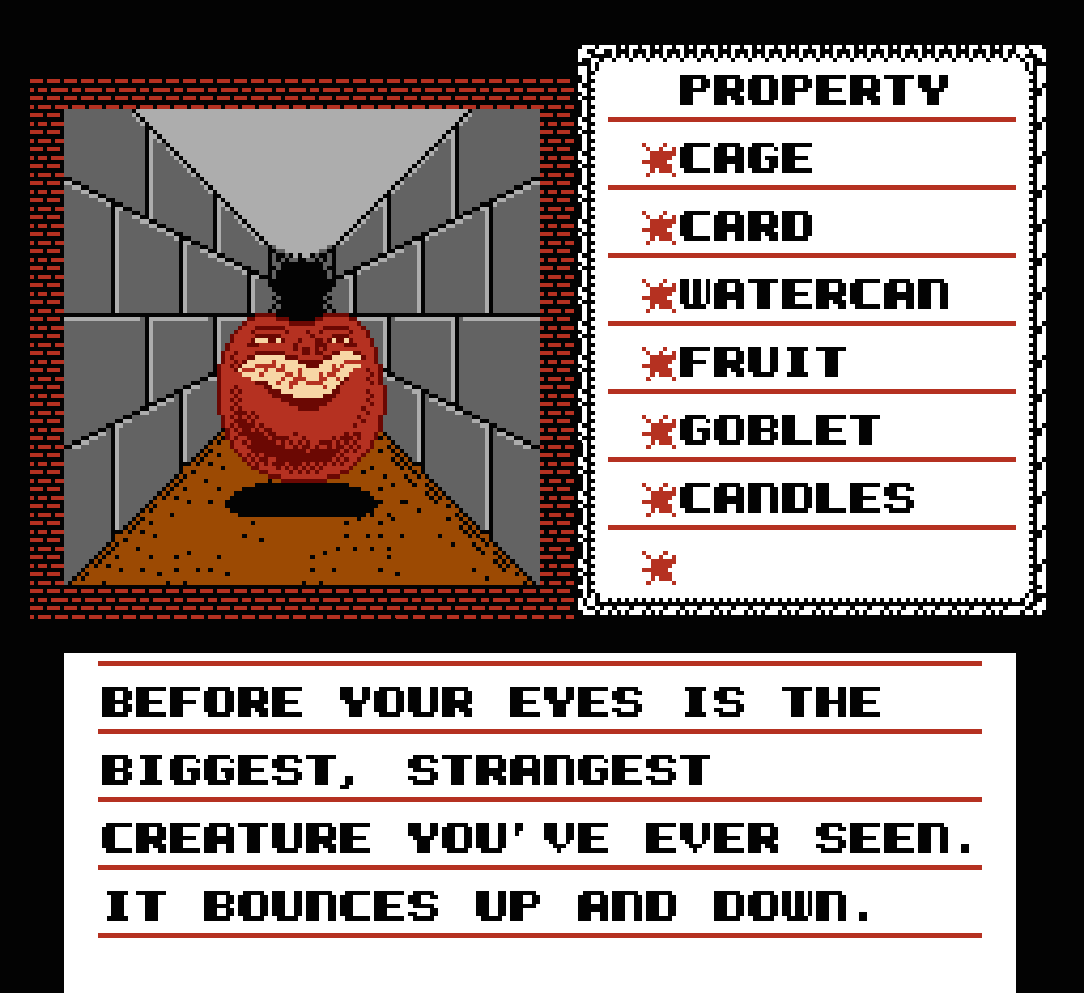

Throughout the three games, you traverse a strange landscape mainly reminiscent of a hotel, with a few outdoor environments, uncovering clues about the land of lucid dreams and its fearful inhabitants, the Shadow People. There's not very much story here, and it gets a bit confused in the third instalment with the introduction of a new antagonist, but what Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep does well is atmosphere. Since you know this is all "just a dream," it helps explain a lot of the strange architecture, and it also gives you a sense of false safety.

There's an exceptionally well-done sequence at the beginning of the second game where you make a trip to a library to research other peoples' experiences with the dream world, only to find that you have fallen asleep at some point and are now trapped in the realm along with the dreaded Shadow People. It's very subtle and the transition is well done. I know I said earlier that saying "it was a dream all along" is terrible, but here, the assumption is that you've played the first game, understand that dreams are a key plot point, and the turn is not lazy writing, but skillful development.

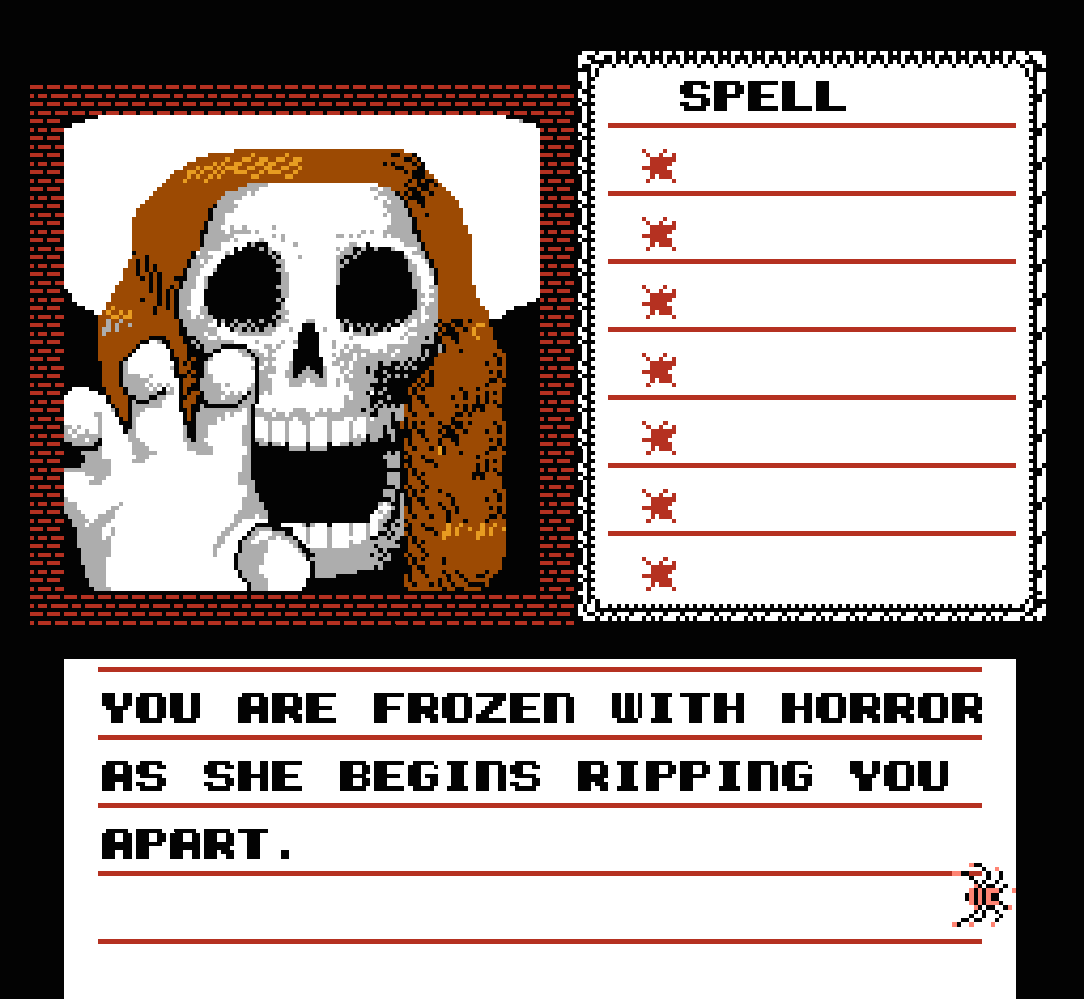

The stakes, unfortunately, are not wholly clear until partway through the second game, but in the third game they are made especially real and terrifying. That game kicks off with a great moment where you wake up, in bed, unable to move. You gradually become aware of the silhouette of a figure looming at your feet, standing in grim silence as you struggle to make your limbs come to life. Then, it lurches toward you, shrieking horribly.

The whole sequence, incidentally, bears an eerie resemblance to the tale of Everything is Scary's own Peter Counter... Coincidence? Maybe..

It's clear that, with Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep, Scriptwelder is creating work from a place of personal experience and love of a genre. There are visual callouts to horror classics all over the place, mixed in with environments familiar and alien. It's a short experience even spread out over three games, but it's a memorable one. What at first seems like a retread of clichés is in fact a rewarding experience, and though dreams are well-explored territory, Scriptwelder proves they are worth going back to again and again. For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come...