Horror by Numbers: FEAR EQUATION

The plot setup for Screwfly Studios' Fear Equation sounds like the ultimate wet dream combo of Snowpiercer, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Stephen King's The Mist.

Read MoreThe plot setup for Screwfly Studios' Fear Equation sounds like the ultimate wet dream combo of Snowpiercer, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Stephen King's The Mist.

Read More

It's kind of crazy to think about the nostalgia people hold for the classic sci-fi movies of the 70's and 80's. It's actually kind of daft. Most of the big franchises - Terminator, Robocop, Alien, etc. - had, at BEST, two good movies to their names. Basically every one of these series has spewed out dreadful sequel upon dreadful sequel right up until today (excepting, of course, the beyond-excellent Mad Max: Fury Road - OSCAR ROBBED AMIRITE?). Alongside these sequels Hollywood has sucked on the the nostalgia tit until it hardened into a dead stalactite, commissioning official novel tie-ins, comic books, and - you guessed it - video games, most of which have been just as wretched as you'd expect. So, when I heard about Alien: Isolation, I greeted it with just a slight tad of apprehension. How did I ultimately find it? Well...

Read MoreMyth II: Soulblighter is a great sequel in every sense. It finds that so oft-missed sweet spot of keeping enough of the original product while bringing in new content, smoother gameplay, and nice little touches that flesh out an already well realized world.

Read More

I'm not entirely sure where the idea of an Undead Army originally came from. There are depictions of animated dead all throughout history. Skeletons as the grim reaper, zombies in voodoo culture, banshees haunting the Irish countryside. In terms of depicting them as an organized fighting force, however, that seems - to my limited knowledge - to be entirely the realm of fantasy. Jason and the Argonauts battled skeletal warriors, Ash fired up his chainsaw against the Army of Darkness, and of course we all know the undead legions of Dungeons and Dragons and in the Warhammer world. For me though, there is no finer depiction that fully realizes the might and terror of an undead horde than Myth: The Fallen Lords.

Read More

(image via Alpha Wave Entertainment)

There is an inevitability of death that gives your pessimism strength. If you’re the kind of person, like me, who doesn't believe in an afterlife or inherent human significance, then the topography of time begins to feel less like a path and more like a pit. There’s a whole way of living your life where all you do is fall.

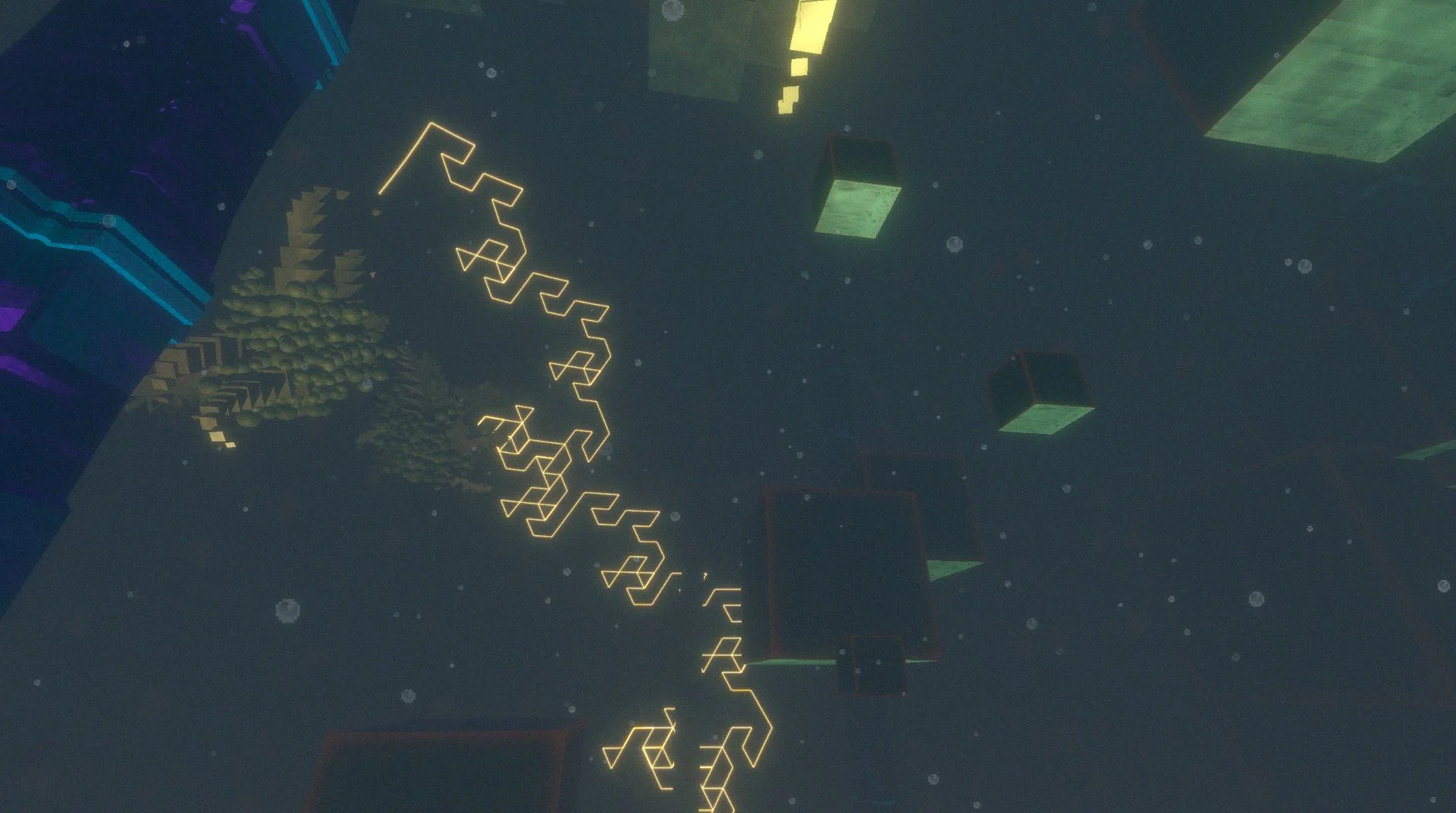

Euclidean, an atmospheric horror game best experienced through the Oculus Rift VR headset, embodies the cosmic futility of the falling lifestyle. Mostly it achieves this through its central gameplay conceit: in Euclidean progress is made as you fall through abstract Lovecrafian dreamscapes. You can see your feet dangling below you as you plummet and sink, slowly maneuvering to avoid the geometric demons that threaten to obliterate you on contact.

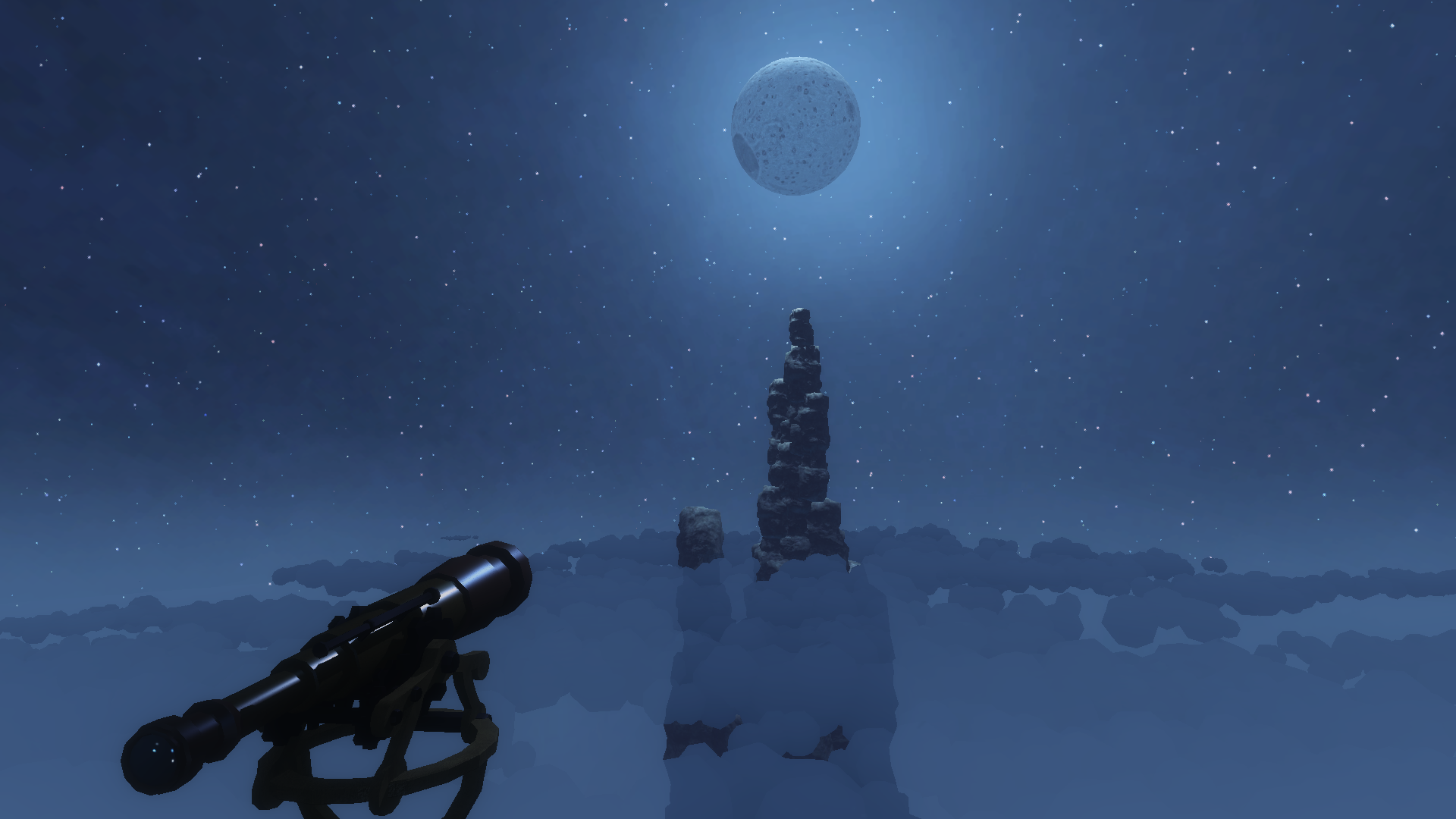

The game's narrative also unfolds vertically. You begin atop a mountain. A telescope is nearby, it is nighttime and you have just finished painting a neighbouring peak, overtop of which hangs a full moon. If you stare into the face of the bright orbiting rock, it appears to get closer until reality dissolves around you and you begin to move downward.

As you dodge the objects in your path, a disembodied voice taunts you. Its language is prohibitive and antagonistic. It tells you that you ought not to have come to this strange place and asks you the sort of questions that would drive a Miskatonic scholar straight to the asylum.

As you fall through various strata of abyss, it becomes apparent that the end of the game will not be one that you can return from whole. Euclidean is a game of annihilation. You dodge threats and persevere through significantly difficult scenarios only to find death in the end. There is nothing beyond what lies at the bottom of your journey.

Euclidean’s greatest achievement is its ending. Bathed in white light, you are made to feel rewarded for your masterful navigation of the demi-void, presented with the images traditionally associated with heaven and spiritual enlightenment (think the ending of Journey). But of course, there are no happy endings in a universe not made for us. No, all of your semi-purposeful descent was into the gaping maw of something you can’t understand, and which might not even be hungry, but nonetheless, will accept you in its tentacular embrace.

The fall always leads to an end, not unlike the sort that might find you on your way down—the endings we call failure. But like Sisyphus, we take the journey anyway. We sink through the fog and pulsing blackness, filled with questions and fear, because when we’re alive and falling, we might as well take in all the wonderful horrifying atmosphere

When I first read Harlan Ellison's 1967 short story "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream," I wouldn't say I enjoyed it. It's not really the kind of work that exists to be enjoyed, so much as appreciated. Preferably with a nice, hard, glass of whiskey and a pillow to cry into afterwards.

Read More

I don't know if it's possible to overstate the affect that Minecraft has had on modern video gaming. It is now the third best-selling game of all time, only behind Wii Sports, which came packaged with the Wii, and Tetris, which is...well, Tetris. It is basically available on every platform known to man, it is a productivity killer, a creative space, a child's development tool, an architect's daydream, a LEGO product...the list goes on. The monumental impact of Minecraft is felt in numerous clones and offshoots that have all attempted, to varying degrees of success and failure, to capture that perfect balance of creativity, "sandbox" gameplay, survival, and pure imagination.

To me, the one that has succeeded best at capitalizing on the craze while also becoming it's own unique entity is Terraria.

Read More

Of all the various ways we as a species have come up with for self-annihilation - nuclear war, zombie apocalypse, ecological disaster, etc. - I think the one that scares me the most is a global pandemic.

Read MoreTim Schafer occupies a sweet spot both in gamer culture and in my heart. In the former, because he is one of those designers that we point to as a sticking point in our ongoing battle of "video games are art." In the latter, because he co-created or created the games that, in the formative years of my life, forever instilled in me a love of point-and-click adventure.

Read MoreSir, You Are Being Hunted is a game that epitomizes the phrase "truth in advertising." In it, you play a Sir (or Madam (and yes, you can actually change it)). You are being hunted.

Read MorePlaying through Among the Sleep, I was reminded of a quote from the Silent Hill film adaptation. Yes, stinky as that movie was (as, let's face it, every video game film adaptation always is (but by all means, keep holding out hope for Warcraft, you poor saps)) it did nail one thing right: "Mother is God in the eyes of a child."

That being the case, the natural followup question is: who is the Devil?

The answer, at least as far as Among the Sleep suggests, might not be what you think.

Read More

I don't know if I can fully articulate the profound impact that Frictional Games has had on the internet.

Read More

Horror isn’t the first word you would use to describe the Metal Gear Solid series of video games – a long running, super popular stealth action series created and directed by Hideo Kojima. Convoluted, sci-fi, self-aware, political and pacifist are better adjectives for the game franchise about the consequences of ideology and war-based economies. Smart but campy, Metal Gear Solid often finds mileage in the supernatural, but rarely trades on fear. And that’s why the 43rd mission in the latest entry, The Phantom Pain, is so remarkable: it scared me to the core.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain puts you in the role of Big Boss, a war hero turned global terrorist threat, during the the period in his life when his moral alignment ostensibly shifted. The game begins with Big Boss waking from a nine year coma caused by a helicopter explosion, and then proceeding to build a nation of soldiers to help perpetuate a war economy for ideological reasons. The whole thing is really convoluted, so for the sake of examining the horror in mission 43, all you need to know are the following points:

Big Boss has a piece of shrapnel lodged in his skull, making him look demonic and also messing with his memory.

Big Boss is well respected among his nation, lauded as the very embodiment of their ideology which they see as noble.

A major aspect of the game is capturing enemy soldiers you encounter and recruiting them to join your military nation. They provide you with in-game bonuses and when you return to your base, the characters you have recruited are around and interact with you. They have names and hobbies and hopes and dreams.

A key aspect of Metal Gear Solid V’s story revolves around a lethal vocal chord parasite that has become weaponized in a genocidal plot to eliminate certain languages from the planet. It is invisible, it is lethal and it has some kind of rudimentary intelligence. The parasite can learn a language and then go on to exclusively inhabit and kill its speakers.

When episode 43, titled “Shining Lights, Even in Death” is unlocked, near the very end of the game, you are called back to your home base. The vocal chord parasite has evolved immunity to the vaccine you previously developed to prevent its infection and there's been an outbreak on your isolated quarantine platform. You, in a gesture of leadership, enter the sealed off area alone in order to investigate.

The level itself is framed as horror. Screaming people, bloody trails, the occasional begging for help. Emergency lights illuminate the halls in an eerie fashion as you look for a person that might hold the key to identifying the infected. When you finally reach the soldier in question, it’s already apparent what lays ahead of you. He dies and you obtain specially engineered goggles that can detect the parasite in people’s throats. Then the screaming starts.

The epidemic horror is ratcheted up immediately after you gain the ability to detect the parasites. You learn that people infected by the parasite are compelled to seek fresh air in service to the bug’s propagation. The stakes are apocalyptic. A gate door to the open air frames a few birds as potential vectors of the final plague as some of the infirmed begin to spasmodically run toward the only exit thirsting for the gulp of oxygen that will end humanity. The game, for a moment, transforms into a zombie story as you are forced to murder familiar faces as a means to protect the world from a climatological threat.

Simultaneously, a great trick is pulled on you, the player. Each person on your base, including those in your quarantine, contributes to the in-game economy. As such, it is important for the player to know when one is taken out of commission. To facilitate this, the game announces staff related events (getting sick, getting injured, getting into fights, dying) with tiny text notifications on the screen accompanied by the stat modifier describing how their departure affects your war business. Therefore, as I shot each zombified member of my hand picked team, I received this message:

Staff Died [Heroism -60]

Once the most zombie-like individuals of my team were dispatched, I descended back down into the dark facility, wearing the new goggles so that I could see who was infected. Sure enough, every human I encountered on the way up, I was forced to shoot dead on the way down. Every person a friend, every friend a bullet, every bullet a statistic.

As this happens the game’s immoral scientist character is screaming at you over wireless. He’s says that you are killing your family, storifying your plummeting heroism statistic by contextualizing your actions as not in tune with the legend of Big Boss. You are a traitor to your family and a traitor to yourself.

Finally, you enter a room with the last remaining infected members of your personal army. They know what awaits them and they respect you. Big Boss, after all, is a man who represents the ideology that they were already willing to die for. Each man and woman in that room sands and salutes you as the game makes you shoot them all in the head. It is heartbreaking, and I would be lying if I told you my eyes weren't filled with tears as I took control of the avatar of these people’s hope before virtually executing them.

The mission, on face value, is horrific. That’s plain to see. The horror tropes employed effectively portray the stakes of the situation, the climatological threat is the type of invisible unhuman entity we instinctively recoil from, and the rock-and-a-hard place moral decision to kill the infected is the apotheosis of a certain kind of nightmare. All of this is made more painful through the fact that video games are a “lean forward” medium (a term coined by developer Cliff Bleszinsk) – the horrific events in screen can only happen with your participation. No covering your eyes. No hiding under a blanket.

That having been said, the truly masterful stroke of horror in “Shining Lights, Even in Death” is retrospective. After the mission is completed and the deceased are cremated, the final piece of the story can be unlocked. It’s a flashback. You play through the very first level of the game from a different perspective and it is revealed that you are not, in fact, the legendary Big Boss. You’ve just been made to look like him. You have built an army in his name, all the while thinking you were the legend himself, but infact you were just a nameless soldier.

Upon the reveal, I was presented with a terrible balance of emotions. At once I was thrilled – not only was the twist meaningful on a series-wide scale, but I had long suspected this character was not Big Boss so I felt like a smarty pants – and I was also ill. There was a knot in my stomach as I listened to the real Big Boss describe the true events of the game. I was transported in my mind to that dark, blood spattered room, with men and women just like me saluting their hero, who wasn’t even there, as a stranger took their lives away.

When I sat down to write about Sunless Sea, I'll admit I had trouble organizing my thoughts, which, in a way, is somewhat appropriate. This is definitely the most surprised I've been by a game in a while, and in the best way possible. It also bears mentioning that Peter played this game a while before I did, and highly recommended it to me (in fact, he's remarked to me that this could be his pick for Game of the Year). I have to say, I can't thank him enough for doing so.

Read More

When I first played through Outlast, I was reminded of a chapter from Max Payne II, entitled "A Linear Sequence of Scares." The Chapter and Title take place in anda funhouse, which Max, in his usual, noir-esque way, refers to as "a linear sequence of scares. Take it or leave it is the only choice given. Makes you think about free will."

This was my experience with Outlast.

Read MoreDoes anyone else remember the show The Storyteller? That amazing, short-lived TV show in the 80's from Jim Henson?

Essentially, the show was an anthology of classic folklore and fairy tales, hosted by the eponymous Storyteller (played by John Hurt and later Michael Gambon) and his ever-present dog companion, voiced and operated by Brian Henson. And it was GREAT. This show was imaginative, colourful, dark and brooding at times, bright and cheery at others. It was propelled forward by a simple premise: aren't the strange and wonderful things we dream up COOL? Folklore is a goldmine of imagination. Dragons, ogres, trolls, fairies...and perhaps the most dazzling thing of all is that it's still growing.

True, it is tempered by modernity's current wave of cynicism, but even against the tide of internet skepticism, we have people dreaming up creatures and stories and myths. And we call them Urban Legends.

One such Urban Legend - one that is fully acknowledged to be a creation, not a tale with any basis in real life events - is that of the Slender Man.

(via Wikipedia)

Slender Man is the freak-child of a Something Awful forum contest, where participants were asked to photoshop pictures with their own ideas for a paranormal occurrence. Eric Knudsen entered an amalgamation of the ideas of Stephen King, H.P. Lovecraft, and the Tall Man character from Phantasm. Depicted as a skinny, hugely tall, blank-faced man in a suit, the Slender Man has oversized arms and is usually accompanied by black tendrils growing out of his back.

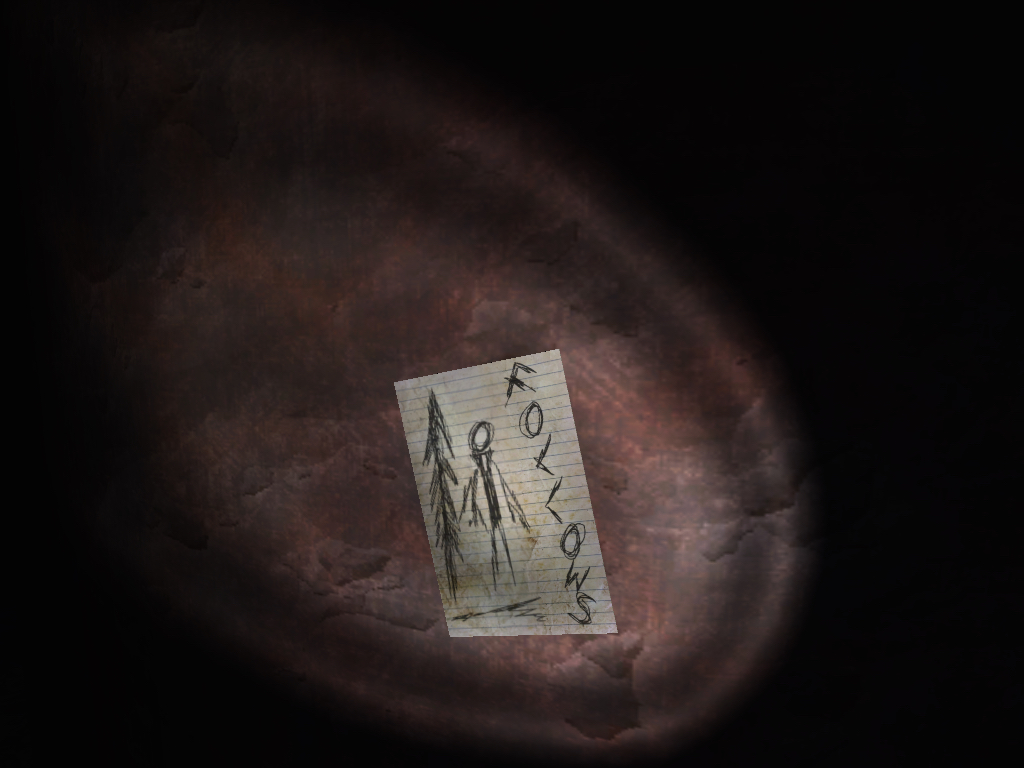

Knudsen's creation struck a chord with the internet, and since his debut in 2009, Slender Man has been the product of fiction, videos, mockumentaries, and - you guessed it - video games, the first and perhaps best known of which is Slender: The Eight Pages.

In Slender: The Eight Pages, you play someone dumb enough to go looking for Slender Man in the woods. At night. Alone. Because hey, you ain't 'fraid of no stupid Urban Legend, right?

Your goal in the game, which takes place in cozy first-person view, is to track through the pitch-black woods with your flashlight, seeking out eight pages which give clues to the mythos around the Slender Man. Naturally, Mr. Slender Man don't take too kindly to this, and he stalks you down for the purpose of...well, I'm not entirely sure. But it ain't good.

The pages you find contain such helpful information as "Always Watches - No Eyes," "Don't Look, Or It Takes You" and simply "NONONONONONONONONONONONO." (had to count to make sure I got the right number of "NO"s).

For such a simple game, Slender: The Eight Pages sure does work well. My favourite story about it involves a friend "gifting" it to another friend. Hours later, the gifter received this text from the giftee: "F--K YOU. I wanted to sleep tonight."

What makes the Slender Man such a compelling figure for the internet, and for pop culture, is his malleability. Since he is rather loosely defined, he can flex to meet the needs of the content creator, and, for that matter, the audience. Like I said, I don't know WHAT the Slender Man does to you when he finds you. I only know that the screen goes all blurry, there's a horrible screeching noise, and darkness.

It is that malleability that I think helps contribute to his enduring popularity. This is echoed in his physical appearance: the faceless entity is one we assign our own meaning to. His suit is merely an indicator of a being adopting the cultural norms of the time. His gender is an assumption of that costume; perhaps he is genderless.

The canon of Slender Man is constantly growing and shifting, an apt metaphor for his very existence as a creation of the internet, itself a semi-organic beast of formless, evolving identity. What will you contribute to Slender Man?

It's difficult to talk about Lone Survivor without spoiling the surprises and turns it weaves through on its way to a poetic, spectacular finish.

Suffice it to say the plot, as presented, is an elaborate deception. Your character is the titular lone survivor of a mysterious apocalyptic event, the nature of which is murky and the effects of which are even murkier. It seems as though the better part of humanity has been infected with some kind of strange virus, mutating them into into mindless monsters that feast on rotting meat and wobble about like the nightmare demons in Jacob's Ladder. Taking refuge from these beasts, your character has holed himself up in his apartment and wears a surgical mask to keep their sickness off of him.

This isn't the only effect of the apocalypse, however. Many parts of the apartment building have been destroyed. Walls are exploded inwards and outwards, as if from a series of explosions. Other parts are covered in Ridley Scott Alien-esque goo and slime. Most of the background details you see show signs of advanced decay: rotted mattresses, rusty beams, crumbling structures.

To survive this situation, you proceed through the apartment complex, gathering food and other supplies, trying to find others, and avoiding or confronting the monsters. You are contacted periodically by someone via radio who calls themselves "the Director," a cryptic figure who speaks in riddles and somehow drops supplies for you. In between forays into the eternal darkness of the apartment building, your character's fragile mental state is sustained by sleeping in your own bed. The twist is that you are often given a choice of medication to use before hitting the hay: the blue pills, or the green pills (there are also red pills which keep you awake longer).

In this medically-induced sleep, your choice of pill also defines your choice of dream. Without giving too much away, these dreams will gradually determine the direction of your character's ultimate fate.

The ever-present medication, coupled with the clues of your surgical mask and the state of the world around you, should provide ample clues that not all is what it appears. That said, it is never explicitly stated just what Lone Survivor is really about, so it is completely open to interpretation.

There is, however, one more glaring clue: the title itself.

The words "Lone Survivor" seem, at first, quite literal. Your character is the lone survivor of the plague. What if, however, we were to take these terms in a more medical fashion?

Survivor Guilt is defined, bluntly, in the Dictionary as: "feelings of guilt for having survived a catastrophe in which others died." As an extension of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, this mental state of being is marked by severe depression, potentially suicidal thoughts, and in some cases by the sufferer blaming themselves for the occurrence that caused the deaths of those around them.

In Lone Survivor, you are positioned as being, quite possibly, the last human being in existence. Whether this should be taken literally or not is in the eye of the player. What is certain is that your character is struggling with a terrible feeling of fear and despair that only people who have been through deep, fatality-involved trauma will understand: the fear of being left alive.

How you come to terms with that fear and pain within the game is in your hands.

Will you take the blue pill, or the green pill? Stay awake, or sleep? Shoot the monsters, or duck around them?

Come to terms with your fear, or let it consume you?

The human condition is defined by our shared experiences, desires, and life events. We are all born. We grow. We die. In the brief period of our lives, we are defined by our instincts. The instinct to survive. The instinct to breed. And the instinct to be curious.

It's a natural resting point for us to question our surroundings. Perhaps it ties back to the survival instinct; after all with knowledge comes power and the ability to survive with greater ease. Discovery leads to invention. Still, with our lives already quite comfortable, we strive for the unknown. We go into the dark places just to see what's in there.

So what happens when you lock us away and throw away the key? If you put someone in a room, and provide food, shelter and clothing, why would they ever want to leave the room? Because they HAVE to. There's a driving, burning need to be free to explore.

Adventure game makers have played on this instinct for years. Indeed, this adventurous instinct has spilled over into real life as well, with companies creating scripted "Locked Room" scenarios. People are paying to be given the experience of being trapped in a room, to feel the thrill of getting out. Escape the room. That's the goal, at all times.

So what happens when you have to fight that instinct?

You get Scriptwelder's Don't Escape series.

In the first instalment of Scriptwelder's little series on turning the "Escape the Room" formula on its head, you are a werewolf. That probably seems pretty on the nose, but that's what I love about this little game. You play a person cursed with the standard trope: full moon, gruesome transformation, bestial rampage, etc. But you're not a bad person. You don't want to hurt people. To that end, your goal is simple. You must lock yourself up with ropes, chains, blockades...anything you can find. You have found yourself a remote cabin suitable for this purpose. You have until nightfall to restrain yourself as much as possible.

Like Scriptwelder's Deep Sleep series, the Don't Escape series are point-and-click adventure games. You explore the cabin, finding useful tools and items to help in your goal. The tricky thing is that in some cases, items are hidden in unexpected places, or don't act exactly as you might expect (one of the first keys you find, for example, does not fit an obvious locked chest).

What I really enjoy about Don't Escape 1 is that, in the end, your efforts are measured by a scale. When the night falls and you transform, the werewolf's attempts to break free are listed. It chews through the rope. It struggles with the chain. And if you screw up, it mentions that too. Maybe you left the window open. Maybe you didn't lock the door, even if you closed it. These things give you clues to completing the game to 100% on your next playthrough. It's immensely satisfying.

If I'm being honest, Don't Escape 2 is, in my opinion, the weakest of the series. Why? Because zombies. And zombies have been done to death (pun most definitely intended).

So in this instalment, you are a survivor of a zombie outbreak trying to survive yet another night in a horrible post-apocalyptic wasteland. When night falls, the zombies come calling, so you have only 8 hours to prepare your little fortress, with or without the aid of others.

This game does have some neat innovations over its predecessor, with a huge variety of ways to emerge victorious. There are moments where you have to make key choices that will affect the outcome. Do you allow your friend Bill, who has been bitten, to live? Do you use the fuel you discover to power a generator, or a car?

What disappoints me is that unlike the previous narrative reasoning for trying to prevent your own escape, which was interesting and unique, this one falls back into clichés and tropes all too familiar. There's no real surprises here. All the usual beats are hit in all the usual ways, and this is less about defying natural instinct, and more about playing right into survival instinct.

Finally, we have Don't Escape 3, to me the strongest and most unique of the series. It kicks off with a jolt to the senses. You're in an airlock, and if you don't do something right away you will have all the open space you want.

When I first started playing this game, I suspected that might be the play on the "don't escape" theme. You do not WANT to escape the comfortable confines of your ship, derelict though it may be. It and it's comfy steel walls are the only thing keeping you from a horrible death.

I was pleasantly surprised to discover, however, that the narrative leads to something much more interesting. I don't want to give away too much, but what you find in the final piece of Scriptwelder's trilogy involves a trail of bodies, an alien lifeform, and a decision between self-preservation and the greater good.

What makes the Don't Escape trilogy unique in the horror game landscape is that it involves defying your natural gamer chops. Generally speaking, horror and survival are so closely linked that people almost always refer to them as the "survival horror" genre. Here, though, you're fighting for more than survival, or curiosity, or exploration. Here, you're fighting your basic instincts.

"It was all just a dream."

Raise your hand if that line, or a slight variation thereof, sends you into paroxysms of rage. In modern media, this is one of those unforgivable clichés, a flimsy explanation for events told in a fictional narrative that has been so thoroughly trod over that it could be repurposed as a doormat. There was time when it was charming, even fresh, but that time is roughly about the same period when Dorothy and Toto were traipsing around Oz. So if you want to set your work in a dream, you'd better bloody well have a good reason, or at the very least be bringing something fresh to the table.

Scriptwelder, thankfully, does, in his series Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep.

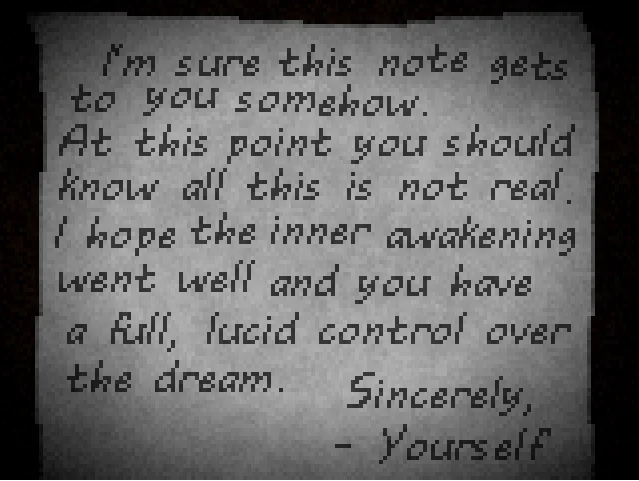

Yes, the title(s) is a bit of a lead brick, but what sets this little series apart from other "dream exploration" horror games I've played is the upfront acknowledgement that you are dreaming. More to the point, you are dreaming deliberately. You play an unnamed person who is fascinated by the concept of lucid dreaming, and is convinced that tapping into this space of imagination and self-awareness holds some strange power and may, in fact, be interacting on some level with reality.

The games are all point and click adventure games, which hold a special fondness in my heart, and feature the same style of graphics as The Last Door, all pixelly goodness. The main difference, however, is that the third-person perspective of that series is replaced here with a first-person view more akin to Uninvited.

Throughout the three games, you traverse a strange landscape mainly reminiscent of a hotel, with a few outdoor environments, uncovering clues about the land of lucid dreams and its fearful inhabitants, the Shadow People. There's not very much story here, and it gets a bit confused in the third instalment with the introduction of a new antagonist, but what Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep does well is atmosphere. Since you know this is all "just a dream," it helps explain a lot of the strange architecture, and it also gives you a sense of false safety.

There's an exceptionally well-done sequence at the beginning of the second game where you make a trip to a library to research other peoples' experiences with the dream world, only to find that you have fallen asleep at some point and are now trapped in the realm along with the dreaded Shadow People. It's very subtle and the transition is well done. I know I said earlier that saying "it was a dream all along" is terrible, but here, the assumption is that you've played the first game, understand that dreams are a key plot point, and the turn is not lazy writing, but skillful development.

The stakes, unfortunately, are not wholly clear until partway through the second game, but in the third game they are made especially real and terrifying. That game kicks off with a great moment where you wake up, in bed, unable to move. You gradually become aware of the silhouette of a figure looming at your feet, standing in grim silence as you struggle to make your limbs come to life. Then, it lurches toward you, shrieking horribly.

The whole sequence, incidentally, bears an eerie resemblance to the tale of Everything is Scary's own Peter Counter... Coincidence? Maybe..

It's clear that, with Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep, Scriptwelder is creating work from a place of personal experience and love of a genre. There are visual callouts to horror classics all over the place, mixed in with environments familiar and alien. It's a short experience even spread out over three games, but it's a memorable one. What at first seems like a retread of clichés is in fact a rewarding experience, and though dreams are well-explored territory, Scriptwelder proves they are worth going back to again and again. For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come...

People always say that you should do what you love for a living.

I feel like there's some truth to the perception that my generation was raised on that old adage, spoon-fed the belief that anyone can and should be able to do anything. The thing is, though, real is just more complicated than that. Sometimes, we fail. Sometimes, we don't get our dream job. I think what we should learn, from the very moment we're old enough to have an idea of the things that make us happy, is that we should make time for the things we love, even if we don't get to do them all the time.

I love writing. I really do. I can honestly say that I've wanted to be a writer since I was in Elementary School. I still have the hilariously bizarre comic strips that I made as part of a class project. "DUCKMAN" my little hero was called (no relation, I promise, to the show starring Jason Alexander). I made several Duckman books for class, with varying levels of poop and butt jokes in them. They were a great source of amusement for me, my sister, and my friends (and still are, in some ways, to this very day). It wasn't until I wrote the Grade 6 English provincial exam that I really knew why I loved writing so much.

The exam - which, if we're being honest, should only be loosely referred to as an exam - had only one question on it: write a story based on the prompt as given. In this case, it was a picture of a young woman, eyes wide with fright, and a couple accompanying lines about her being pursued by parties unknown. From there, I took it in the direction of a young man uncovering a Scooby-Doo-esque situation with fantasy touches, with old man impersonating a mythical beast to drive villagers away from his ancestral lands (and he would've gotten away with it too, etc.).

Yeah, it was silly. It was Grade 6. Cut me some slack. Thing is, though, my teacher liked it well enough that she read it to the class. Much to my surprise, they liked it too. I made something, and people felt happy after reading it and hearing it. And that felt...good.

Since then, I've written blogs, plays, stories...and I've only been paid for it maybe 1% of the time. I don't do this because I'm trying to be rich. I do it because it makes me happy.

It is a feeling, I think it is fair to say, that is shared by Scriptwelder, maker of many Flash games, all free to play on sites like Newgrounds and Kongregate. Scriptwelder is a Polish programmer who has been making games in his spare time for the past 5-6 years.

I'm going to be devoting my posts to Scriptwelder's games over the next two weeks, and I wanted to give you an intro that drove home the respect I have for this fellow and his abilities. It's not merely that he makes things for free; it's that they are of a quality and depth that are always surprising and interesting. They are not, by virtue of the interface, of great length or graphically stunning, but what I find time and time again is that they are full of heart. It's obvious when you play one of Scriptwelder's games that it is a project made by someone who genuinely cares about what he does. He isn't doing this for money, or fame. He's doing it because every now and then he has a great idea for a video game, and he wants to share it with the internet.

One such game, which is perfectly apt for the remaining space in this post, is A Small Talk at the Back of Beyond.

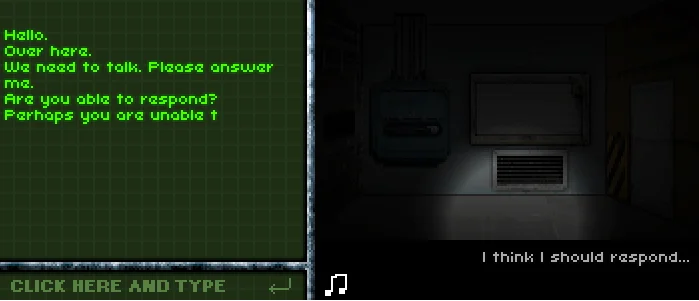

In this game, you awaken in a strange place in pitch darkness. Across the room, a green monitor draws your attention. Text appears...someone is trying to communicate with you. The game invites you to answer back.

From there, the game is essentially a text-based RPG, albeit one with a small graphic display. You talk to the mysterious person on the other end of the line. You question them about your surroundings. You might play a game with them. But ultimately, your path - driven by the natural curiosity of the human mind - will take you to a final, powerful choice.

A Small Talk at the Back of Beyond lives up to its name. The entire game can be played in as little as two minutes. In that time frame, it somehow manages to find time to be emotional resonant, driving down to one of life's most basic fears (which I will not reveal here for sake of spoiling the surprise). It's not meant to be a widely distributed commercial project. It's not something which I think anyone would ever charge money for. It's a little snippet meant to provoke an emotional response from an audience. And that's enough.

Next week I'll take a look at the first of Scriptwelder's trilogies: Deep/Deeper/Deepest Sleep.