Ten Reasons Friday The 13th Part 2 Is Better Than The First Movie

Friday The 13th is a genre classic, but the first sequel is way better and here are ten reasons why.

Read More

Friday The 13th is a genre classic, but the first sequel is way better and here are ten reasons why.

Read More

In the 1976 horror film The Premonition, women's struggles are the main focus.

Read More

Between vampires on Penny Dreadful and venereal disease on The Knick, it's a tough call to decide which is worse.

Read MoreWith Game of Thrones Season 6 just around the corner, and with hype engines set to full ludicrous speed, I felt that a look at the show's chief antagonists and their bowel-loosening terror was appropriate.

Not the Lannisters.

Not the Freys.

Not the Boltons.

No, the true enemy of all Westeros (and possibly parts beyond) finally reared its ugly head in full-fledged fashion towards the tail end of Season 5, and boy was it a doozy. All hail The White Walkers!

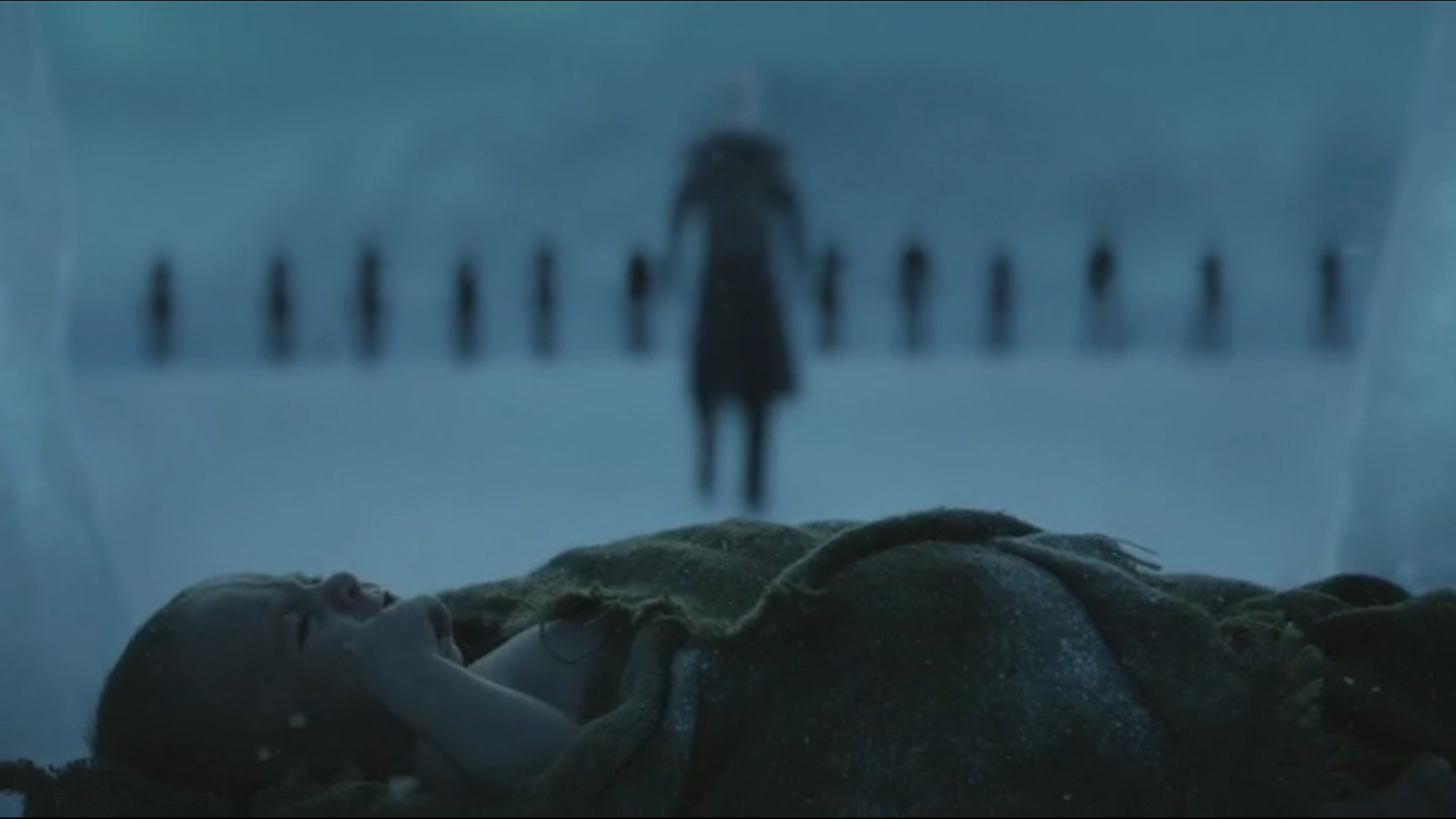

Hardhome is deservedly one of the most critically-acclaimed and highest-rated episodes in the series. It features some marvellous character work positioning key players into some exciting places: Arya is poised to become a super-assassin, Cersei is informed by Qyburn that "the work continues," and Sansa discovers from Theon/Reek that her younger brothers are still alive. Perhaps most thrillingly, the meeting that every book reader had been waiting for finally happened, with Tyrion putting himself at Daenerys' mercy. All of this would have been thrilling enough, but then the action shifted to Jon Snow and Tormund trekking to the titular Hardhome. It seemed, at first, as though this would be a mere shift forward in Jon Snow's story, as he brings home a fair chunk of Wildlings, while the majority stay. But one sharp left turn portended by barking dogs later, and we got a stunning action set piece that dwarfed the thrill and drama of Blackwater and The Watchers on the Wall.

Even more crucially, what Hardhome did was re-focus the series' narrative into a razor point. The politicking and backstabbery is coming to an end. Fans have lamented that there are very few (if any) "good" people left to root for, and there's a reason for that. As the high lords' battle for control racks up the body count, we can sense the end is near for the crown of the Seven Kingdoms. So the story must turn its attention to the real war: the coming army of the dead. We've had dollops of the White Walkers throughout the series. They've dropped in roughly once a season to remind us that they exist, and that they are coming. These appearances, however, have been more ominous and atmospheric in flavour. The Battle of the Fist of the First Men (or the Fight at the Fist) wasn't even shown in the TV series; only the aftermath was shown. Samwell Tarly caught a glimpse of the army of the dead, but we hadn't seen them in action, aside from the occasional wight.

They were definitely creepy, well-designed and unsettling, but they weren't precisely threatening. They didn't kill any named characters (with the exception of the Wights' unexpected takedown of book-alive Jojen Reed; but no White Walkers were present at that brief engagement), they didn't seem terribly urgent, and Sam destroys one with relative ease. In Hardhome, however, we see the full force of the army of the dead for the first time. What's crucial to this reveal is the incredibly well-paced writing and development of two one-off characters. Most critical attention has focussed on Karsi, the female Wildling leader, but equally important is the introduction and subsequent elimination of the Thenn leader, Loboda.

From a meta-narrative perspective, we would look at these characters as possible additions to fill gaps in Jon Snow's story. Having eliminated the previous Thenn antagonist, Styr, the dialogue seems to suggest we're being given a new thorn (no pun intended, Ser Alliser) in Jon's side. Karsi, on the other hand, seems like a fully fleshed-out ally with motivations and a history with Tormund. The audience could easily be forgiven for being lulled into a false sense of security that one or both of these characters would become a series' regular. So when both of them fall in the White Walker attack, the effect is truly shocking. And also unifying.

It's a very subtle through-line, but by introducing and eliminating an ally and an enemy all in one go, Hardhome demonstrates that in the face of a truly terrifying, unknown force, the petty differences of men matter little. All the backstabbery and grudges in the world won't make an ounce of difference to a foe that doesn't play by any of the usual rules. We've HEARD this sentiment before, from Jon Snow and from others, but to SEE it in action is what makes all the difference. These are aliens who will slaughter every nation, no matter your allegiance. Indeed, the unifying terror of the White Walkers is that they simply don't obey the standard rules that have been established. Every other "monster" in the Game of Thrones universe, from Walder Frey to Ramsay Snow, has a motivation. Ramsay wants to please his father, and be a real Bolton. Walder Frey wants to own the Riverlands. But the White Walkers? We really have no idea what they want. All we know is that they turn life to death, relentlessly, mechanically, remorselessly.

The internet's meme-reaction to the image of the Night's King, standing on the beach, arms spread, is especially telling. "Come at me, Snow" read many captions, in a play on the macho bravado of simple-minded men. The attempt to assign any human emotion to the actions of the White Walker leader (dubbed "The Night's King" by a script leak) is, in a way, the perfect microcosm of the series. In truth, what he/she/it is doing is beyond human understanding. He isn't taunting Jon Snow. He's merely adding the fallen to his ranks. Having accomplished that, he lets his arms fall to his side, and stares after the retreating Night's Watch. There is no glee in his crushing victory, no taunt. It simply...is.

There's a reason that the White Walkers are referred to simply as "Others" in the books (a term that probably wouldn't have translated very well to an audio/visual medium). They are outside of the realms of men. They are the other given form, the stuff of nightmares.

And honestly? I can't wait to see what they do next.

Demdike Stare's collages of sound and imagery provoke responses akin to nightmares.

Read More

The titular beast in the film Sleeping Giant reveals itself in subtle and frightening ways.

Read More

Intruders: what happens when a mental health issue is used as a device to entice viewers into watching a movie about a totally different kind of pathology.

Read MoreThe woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.”

Read More

Baskin is a stunning shock to the system for horror fans. Miss it at your peril.

Read More

When it comes to Man vs. Beast movies, sometimes it's best to leave well enough alone.

Read More

The ending to The Witch is victorious and liberating.

Read More

The dream of the '90s is alive in The X-Files. Or is it?

Read More

What makes a man into a monster?

Read More

What would happen if Fox Mulder met Will Graham, or at least tried to think like he does?

Read More

In the advent of ground-breaking true crime shows like The Jinx and Making a Murderer it seems utterly bizarre that a show like Crime Watch Daily exists.

For starters, each episode opens like Inside Edition, the TV show equivalent of those annoying click bait Buzzfeed headlines that clog your Facebook feed with crap like “You won’t believe what happened when this man ate a cheese sandwich!” The barrage of “if it bleeds, it leads” style headlines on Crime Watch Daily provide viewers with very little useful information about actual crime, relying instead on grabbing ears and eyeballs with whatever salacious copy they can conjure. At least you can click on clickbait headlines; you have to sit through an entire episode of Crime Watch Daily to get to the “good” stuff.

It’s bad enough that the Internet is crammed with this kind of junk; do we really need it on our TV screens as well? It’s a relevant question since the Crime Watch Daily set virtually indistinguishable from the ones used by shows like Entertainment Tonight: all glass, chrome, sparkling lights, and giant flat TV screens. The set also looks like a super close up photo of microchips, which ironically only serves to further highlight the distinction that this is Not The Internet.

The idea that a daily TV show would be able to keep up with crime stories in real time as they develop – a market the Internet and 24-hour news channels have cornered – makes the existence of Crime Watch Daily an anomaly in the first place. If they were reporting on the kinds of things that viewers need to know about crime on a daily basis, perhaps an argument could be made that they provide a vital service, but they don’t.

It’s true that we take risks every time we leave the house (or in the case of a home invasion, while we’re there). Depending upon where we live or what kind of job we have, we could encounter a lot of crime: mugging, shooting, stabbing, kidnapping, or sexual assault. These kinds of risks, however, are already covered by local news programs and crime data maps that are available on, you guessed it, the Internet.

Note that I’m not implying local news stations always do a bang-up job reporting on the kinds of crimes we might encounter, but they are at least more qualified to give us a microcast of what’s going on around us than a national program like Crime Watch Daily. The show does have a segment called “Crime Watch Local,” but it only airs weekly, competing with 30 to 40 other minutes of the show’s airtime; therefore, it would be impossible to cover every “local” corner of the United States.

Crime Watch Daily doesn’t even provide any tips or tricks for how to avoid crime, focusing instead on just telling us about it without giving us any insight into what the crime could mean to the viewer on a personal level or what it means to crime in society as a whole. In fact, the show has two specific segments that seem to have been created purely out of some need to make fun of others. “Bad Seed of the Day” and “CrimeTube” are, respectively “a weekly segment profiling a particular criminal and the crime they committed” and “a daily segment… featuring videos of criminal acts, sting operations, police pursuits, and footage of law enforcement activity culled from public doman security camera, traffic camera, and police dashcam footage." Yeah, we have that second thing already; it’s called YouTube.

Sure it might give us a feeling of schadenfreude to witness criminals being caught in the act, but does that serve any real purpose? No, it seems that Crime Watch Daily is merely interested in WATCHING crime, not examining it, not trying to prevent it, not helping viewers get a more profound understanding of it. It’s a spectator sport that takes real tragedies and repackages them into glossy, bite-sized chunks of sugar, providing a quick fix of empty calories.

There is a certain element of fear-mongering on Crime Watch Daily, which feels carefully scripted to highlight the lurid details and the emotional fallout of the crimes it depicts, but the show doesn’t evoke empathy in the same way that seeing a grieving family member at a press conference or being interviewed at a crime scene might. It’s like a ginned-up version of fear that makes people feel like they know what’s going on even though Crime Watch Daily only provides limited information, the kind of thing that people might use to justify racism, classism, sexism, and the intersection of all three.

Crime Watch Daily is fear mongering without the fear, replaced instead by self-righteousness. That’s truly scary.

Mark Duplass's Creep brings the found footage horror film to the next level.

Read MoreJerry seems like a nice guy. He works at a bathtub factory in Milton and lives in the upstairs apartment of an old bowling alley with his two pets, Bosco (the boxer) and Mr. Whiskers (the yellow tabby cat). Jerry is kind of shy and awkward, but his therapist encourages him to participate in planning the annual office picnic. Jerry is also smitten with Fiona, the beautiful English woman who works with him, and hopes that he’ll be able to woo her with his humble charms.

The Voices begins like a sweet romantic comedy with a slightly dark undertone. As Jerry, Ryan Reynolds is less Green Lantern and more Clark Kent. We find out right away that he talks to Bosco and Mr. Whiskers and that they talk back. We figure he’s got some kind of schizophrenia, which is confirmed when he fudges the details about hearing voices and taking his meds. It doesn’t seem like that big of a deal until Fiona is revealed to be something of a self-centered creep and Jerry accidentally-on-purpose stabs her to death.

It’s a shocking scene in a movie that, up until that point, feels like a quirky art-house film. Director Marjane Satrapi and writer Michael R. Perry shift the tone of The Voices in an uncomfortable direction, one that almost feels like it was borrowed from another genre. It’s a stylistic gamble that actually pays off due to Ryan Reynolds’ sympathetic portrayal of Jerry and some straightforward talk about mental illness.

In her review of The Voices, The Spectator’s Deborah Ross doesn’t mince words about how much she “bitterly” resents having to watch the movie at all, describing it as “hateful” and “repellent” and singling out its tone shift for particular condemnation. I have to wonder if we saw the same movie. There are certainly horror films that seem to glorify the killer’s grisly acts or which revel in misogyny for misogyny’s sake (the recent remake of Maniac, for example), but The Voices doesn’t even show most of the crimes that Jerry commits. The majority of his murders take place off screen and he clearly, obviously, and repeatedly regrets the killing.

Terrible acts have been committed by those who have felt compelled to kill because of a mental health condition and many of the victims’ families have a hard time understanding what could drive someone to do those terrible things. I only need to say the names “Vince Weiguang Li” or “Rohinie Bisesar” to evoke a visceral reaction in certain people. The Voices, however, doesn’t ask us to forgive anyone’s crimes; it offers a window into the interior life of someone who commits murder at the behest of the voices in his head. It also shows how even those who aren't subject to delusions have inner voices which can cause immense psychological harm.

The world in which unmedicated Jerry lives is bright and cheery; the world in which medicated Jerry lives is like something out of Hoarders. Without his ongoing interactions with Bosco and Mr. Whiskers, Jerry feels frighteningly and overwhelmingly alone. That’s what taking medication does to him.

No doubt we’ve heard the stories of schizophrenics who don’t take their meds because it makes them feel weird, depressed, different, or miserable. Satrapi and Perry make this visually apparent through the reality of Jerry’s decrepit, disgusting apartment while Reynolds successfully conveys to us what it feels like to be trapped in that dismal world.

His hallucinatory flashbacks to the unfortunate demise of his mother at his own hands are heartbreaking, especially when Jerry’s hateful, abusive stepfather is depicted as exacerbating the situation. How could we not feel sorry for what Jerry went through, none of which was his own fault?

Once the depths of Jerry’s disease and despair have been revealed, the comedy in The Voices feels more like the only way he can escape his tortured existence. It’s the fear of being alone that drives him to resist taking his meds, to continue seeking that fantasy world with Bosco, Mr. Whiskers, and the love and affection of a genuinely nice co-worker named Lisa. It’s a fear that we can all relate to, whether or not we suffer from the delusions of paranoid schizophrenia and it’s what makes The Voices so smart and ultimately, so special.

At some point in the 1990s, before became a horror junkie, I worked up the courage to watch 1978’s Magic. You know, the one where Anthony Hopkins portrays Corky Withers, a ventriloquist for the dummy known as “Fats,” who may or may not have a personality of his own.

That premise is creepy enough: my lifelong dread of ventriloquist dummies (or what Neal on Freaks & Geeks called “figures”) was set in stone thanks to the Howdy Doody that lived at my grandma’s house. The scariest scene in Magic takes place after (SPOILER ALERT!) Corky/Fats kills his agent Ben Greene (Burgess Meredith) and drags the body out into a nearby lake. Greene, however, isn't dead and his unexpected gasps for breath terrified me far more than any of Fats’ shenanigans. The experience was akin to falling into a deep, black hole; it was almost like the utter terror of a panic attack but concentrated into a few seconds. There was nothing else; only the feeling that I was actually going to die of fright.

The idea of dying of fright wasn’t new to me. As a kid, I was a big fan of the William Castle-produced The Tingler, starring Vincent Price. Price portrays Dr. Warren Chapin, who becomes fascinated by Martha, the hearing-impaired wife of a movie-theater owner named Oliver Higgins. Similar to the spirit of death in The Asphyx, “The Tingler” is a parasite that resides within every person. When that person is afraid, the Tingler grows stronger. If that person cannot release that fear, it is possible, Dr. Chapin believes, for that person to literally die of fright when the Tingler crushes their spine.

I was mildly obsessed with the idea not that the Tingler was real, but that a person could actually die of fright. Was this part of the reason I avoided horror films for so long? Or did I subconsciously know that I would eventually become somewhat addicted to them?

Surprisingly, for someone who claimed to be too scared to watch horror movies, I sure did watch a lot of them. And oddly, many of them were simply not scary. It seemed that it was the fear of fear that kept me away. There were major exceptions: Fulci’s The Gates Of Hell, Zelda in Pet Sematary, that part in Jeepers Creepers when the creature realizes Trish and Darry are watching him, when the alien is shown on the roof of the house in Signs. After I learned to relish the feeling of falling into a hole, I began to crave it.

Yet each time that feeling would eventually subside. I became convinced that the filmmakers knew that they had to ease up on the fear factor or it would be too much for viewers to handle, as if there was some precise algorithm to determine how much fear an audience would experience, when they would experience it, and the best ways to hold back to avoid killing them.

The more I craved That Feeling, the more movies I watched in an attempt to evoke it, and eventually it became harder to feel that specific type of fear. Of course, I felt scared watching horror movies, but that specific “falling off a cliff into a dark, bottomless pit of fear” feeling was rare. When I experienced it (like the first time I saw The Descent, for example) I was so terrified I just started crying. I was preventing my own Tingler from killing me by releasing my emotions in a strange and unexpected way.

The most profound example of this was the first time I saw À l’intérieur. I was home by myself, yes, but it was on a sunny afternoon. This film, with scant few jump scares but a veritable ocean of blood made me so scared that I started crying about a half hour in. When I finally stopped, I started thinking that maybe that magic algorithm had been utilized. Yet, the film wasn’t done with me, because it all started up again just a few minutes later, leaving me a literal, sobbing mess long after the credits had ended.

Ladies and gentlemen, I had broken my own fear barrier.

Once that happened, I felt like I could watch anything, thinking I’d probably never get that feeling again. Which is why when it has happened a few times over the next few years (Insidious, “Second Honeymoon” in V/H/S, Session 9), it has been a huge surprise. I still seek out that feeling because despite those few seconds of panic, it is one of the most disturbingly satisfying sensations in the world.

“Kilgrave, in many ways, can be seen as an avatar for all of mental illness… Further developing the comparison, we see through the entire thirteen episodes that the Purple Man’s true power and freedom comes from his ability to stay invisible to the public at large.”

In his Dork Shelf article, “4 Reasons Jessica Jones is the Definitive Post Traumatic Hero,” Peter Counter talks about why the TV show’s representation of PTSD is so accurate, powerful, and important. Jessica Jones, the character, has PTSD. It doesn’t define her, but it does affect her.

Another trait that affects her? Her superhuman strength, which according to the comics, she acquires after an accident involving radioactive chemicals. (This accident is referred to only in passing on the TV series.)

These two qualities present an intriguing dynamic. Since so many superheroes are defined by their superhuman strengths (and weakness, like Superman and Kryptonite), it’s important that Jessica Jones is never depicted as invulnerable. In fact, she’s shown as quite the opposite; she’s shown as human.

Her drinking problems began before she met Kilgrave; in a flashback in episode 5 (“AKA The Sandwich Saved Me”), she is shown quitting what is apparently another in a long series of mind-numbing office jobs, asking Trish how she should add “day drinking” to her resume. Her superhuman strength hasn’t done much for her career options.

That strength made her attractive to Kilgrave, but in the end, it didn’t protect her from him. His invisibility is perhaps more dangerous than if he could actually make himself invisible. In the world of Marvel’s The Avengers, skills like super strength and invisibility are accepted, even if not everyone feels comfortable knowing they exist (see also episode 6, “AKA You’re A Winner!”).

Jessica committed heinous acts while under Kilgrave’s spell, but she was able to fight him off and survive, even if the cost of that survival still presents obstacles to not only Jessica herself, but the other people in her life. She can break locks, bend rebar, fight off several would-be assassins at once, stop a car in its tracks, and kill a person with a single, well-placed shove, but she can’t be rid of Kilgrave’s evil.

It’s the worst kind of fear; living in terror of something that no one can see, something that not even the victim who is suffering can physically touch. What’s more frightening: being physically hurt or being mentally hurt, or to quote The Joker in The Dark Knight, “You have nothing, nothing to threaten me with. Nothing to do with all your strength.”

This idea of the invisible enemy can be also found in The Avengers movie from 2012, when Hawkeye tells Black Widow, “You don't understand. Have you ever had someone take your brain and play? Take you out and stuff something else in? You know what it's like to be unmade?”

Truly, it is a terrifying concept. After a sexual assault, and the subsequent PTSD that ensues, many women wonder if they look different, if people will look at them and see that they’ve been a victim. That feeling of being broken or unmade transforms a physical act into a metaphysical burden.

But the thing about survivors of trauma is that we don’t have to be defined by what happened TO us. Jessica Jones, for all her flaws, shows us that there is a way out, a way to reclaim our minds and our sanity. That fear may be there, but it doesn’t need to define us.

There have been many horror films about nightmares, including one popular franchise starring a guy with a red and green striped sweater, but they all have one thing in common: they clearly announce their intent in their titles. The scariest thing about an actual nightmare is not being able to tell the difference between the dream world and waking life. In that respect, Phantasm stands tall amongst its nightmare movie brethren, and not just because it stars six-foot-four actor Angus Scrimm.

If I had seen Phantasm in 1979, no doubt it would have traumatized me. As a kid who suffered from insomnia, nightmares, and panic attacks, the iconic visuals in the film feed into the typical but frequently debilitating fears of the easily spooked: death, cemeteries, funerals, things under the bad, masked creatures, and of course, the imposing and mysterious Tall Man. Since the main protagonist of the film is a 13-year-old kid, it only makes the creeping terror of Phantasm’s narrative more frightening.

Many classic tales are based on the simple idea that no one believes the protagonist; no one will entertain the possibility that the things he or she insists are happening have actually happened or are even real. While this trope is often utilized with women in horror films—with Let’s Scare Jessica To Death and Don’t Be Afraid Of The Dark being my two favorite examples—there are many examples of fiction when this lack of belief from others plagues a child, such as The Wizard of Oz.

In Phantasm, Mike’s parents were killed two years ago, and his older brother Jody wants to protect him. When Jody attends the funeral of his friend Tommy, he warns Mike to stay home lest it freak him out too much. Mike doesn’t listen and this sets some of the events of the film in motion. As things get more and more dangerous, Jody continually tells Mike to stay home, stay safe, stay away from the danger, but Mike always finds a way.

In the beginning of Phantasm, Mike visits a psychic and expresses concern that Jody is leaving. The film then cuts to a shot of Jody’s car driving down the street. It pulls into a driveway and Mike and Jody get out and while Mike works on the engine, Jody tells his friend Toby that he’s unsettled by the way Mike is always following him around. The movie cuts away from this conversation to show an example of this, and by not changing the visual style of the film or cutting back to Jody having the conversation, it’s difficult at first to know whether this image is a flashback or happening in the present, especially when this is followed up by a continuation of Mike talking to the psychic. Director Don Coscarelli does this frequently throughout Phantasm, using dialogue as a kind of sound bridge between scenes to indicate the fluid nature of reality.

It’s true that Mike always seems to be present no matter where Jody goes: when Jody is riding his bike, when Jody is at a local watering hole hitting on a woman, when Jody is having sex with the woman a few minutes later. This is much like the way that we are omniscient in dreams, bearing witness to the activities of others in situations when were not physically present.

There are a few instances where Mike does something and then Jody does the exact same thing, or vice versa. Mike breaks into the funeral home to find more about the Tall Man, when he is attacked by the dwarves. Later, Jody does the same thing, using the same window to enter the building, and is also attacked. When Reggie takes Mike to Sally’s house for safekeeping, Jody dreams of being pulled through the wall by two dwarves, a scene repeated at the end of the movie, only with Mike instead.

Later, when Mike is lying on the ground after being attacked by the dwarves in Sally’s car, the film cuts back and forth between him on the ground and Jody’s face, almost as if Jody can see what is happening to Mike. Is the Jody of the film just Mike’s dream world version of his brother?

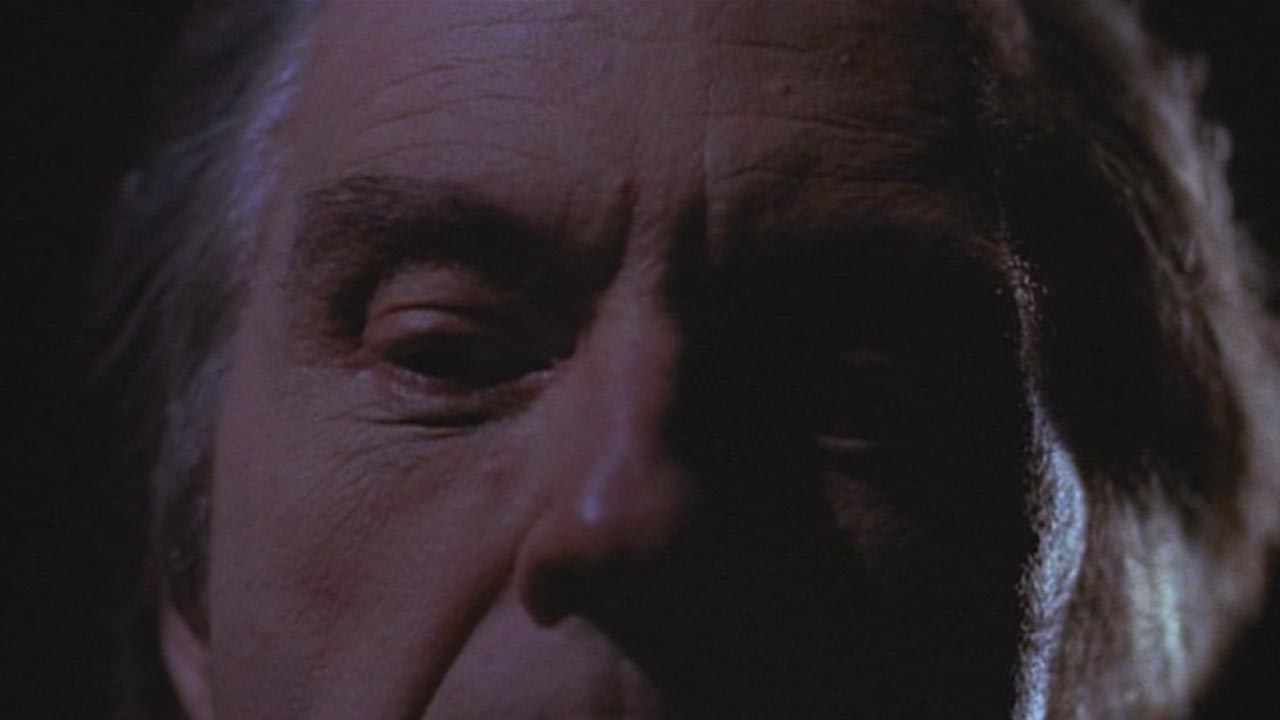

These are not the only two characters blurred together in Phantasm. The Lady in Lavender stabs and kills Tommy at the beginning of the film. A close up on her face cuts to a close up of the Tall Man’s face but this is never explained. This visual is repeated when she stabs Reggie at the end of the film. This is similar to the way characters in a dream often “become” someone else without explanation, or the way that a dream character looks like one person but you somehow “know” they are another person.

Mike is able to prove to Jody that the Tall Man is a real threat when he cuts off his fingers and brings one home. But when he and Jody decide to bring the severed finger to the police, in typical dream fashion, it is inexplicably transformed into a large insect that proceeds to attack them both. Reggie is soon brought into their shared nightmare when he arrives at the house and sees what’s going on.

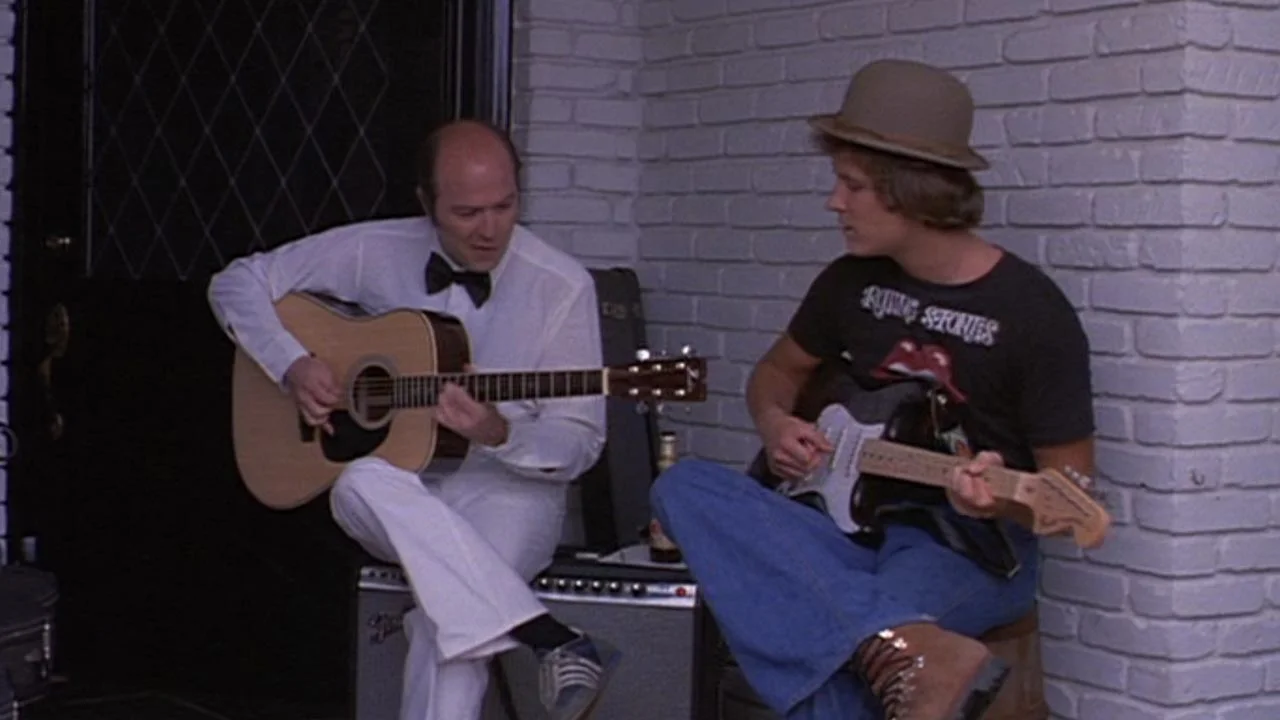

Reggie is not only one of Jody’s best friends, he is also a guitarist and singer, as is shown when Jody is playing guitar and singing and Reggie stops by. Reggie immediately picks up his guitar and starts playing and singing, too, even though this is an unfinished song that Jody has been working on. Reggie’s speaking voice even sounds like Jody’s. At the end of the film, Reggie says that he’ll never be able to replace Jody in Mike’s life but that he’s going to try. Is Reggie real, or just another version of Jody?

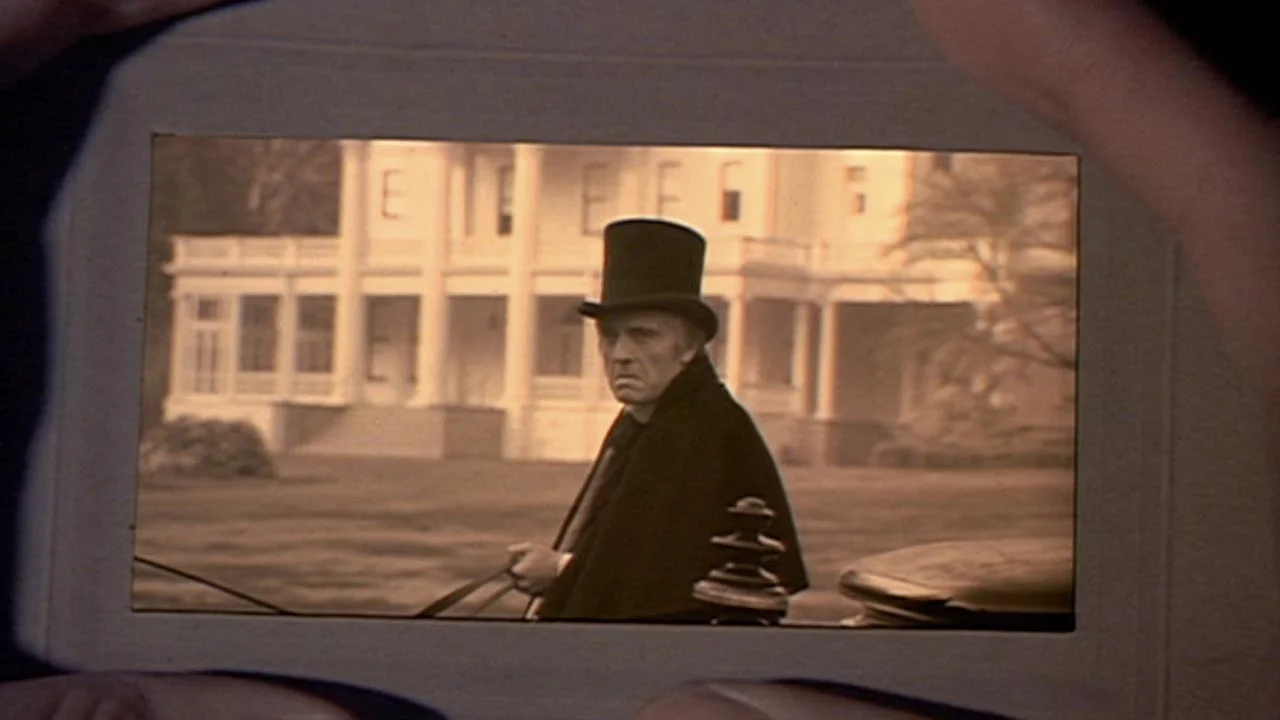

Are the events we see in Phantasm a collection of Mike’s dreams? There are many shots of Mike lying in bed sleeping, which suggest that the entirety of the film is a dream. After all, only in a dream would it be possible for the Tall Man to lift a heavy coffin by himself. Only in a dream would a strange silver sphere hurtle through the air and kill people by piercing their skulls. Only in a dream would corpses be crushed into dwarves to be used as slaves on another plant. Only in a dream would someone bleed yellow liquid when killed instead of red blood. Only in a dream would a photograph move and the person in it look directly into your eyes.

Interestingly, Jody sees the Tall Man before Mike does, but he only registers as peculiar, not evil. It’s Mike who tries to convince Jody that the Tall Man is something supernatural. When Mike sees the Tall Man walking down the street, he’s paralyzed by terror. The Tall Man stands right behind Reggie’s ice cream truck, breathing in the cold fumes, but Reggie—moving in slow motion—doesn’t seem aware that anyone is nearby. Is the Tall Man real or just a figment of Mike’s dream world imagination? The granddaughter of the psychic he visits tells Mike that “fear is the killer” that “it’s all in your mind,” but then she disappears into the mysterious door at the funeral home.

So what is real and what is not real in Phantasm? It’s impossible to decide, which makes it one of the most disturbingly accurate portrayals of nightmare logic in cinema.