SPOILER WARNING: The following article contains spoilers to the ending of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. Proceed at your own peril.

Horror isn’t the first word you would use to describe the Metal Gear Solid series of video games – a long running, super popular stealth action series created and directed by Hideo Kojima. Convoluted, sci-fi, self-aware, political and pacifist are better adjectives for the game franchise about the consequences of ideology and war-based economies. Smart but campy, Metal Gear Solid often finds mileage in the supernatural, but rarely trades on fear. And that’s why the 43rd mission in the latest entry, The Phantom Pain, is so remarkable: it scared me to the core.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain puts you in the role of Big Boss, a war hero turned global terrorist threat, during the the period in his life when his moral alignment ostensibly shifted. The game begins with Big Boss waking from a nine year coma caused by a helicopter explosion, and then proceeding to build a nation of soldiers to help perpetuate a war economy for ideological reasons. The whole thing is really convoluted, so for the sake of examining the horror in mission 43, all you need to know are the following points:

Big Boss has a piece of shrapnel lodged in his skull, making him look demonic and also messing with his memory.

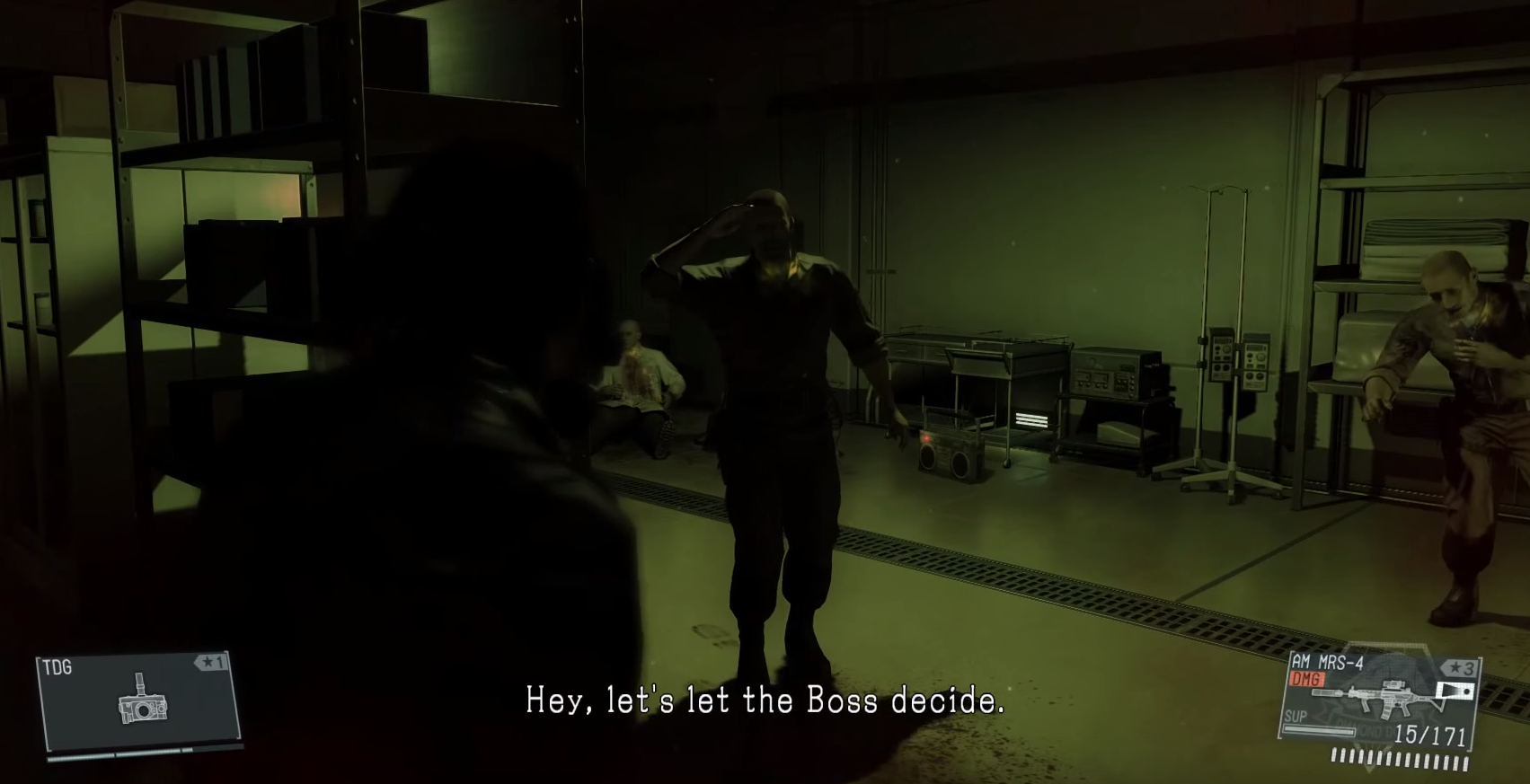

Big Boss is well respected among his nation, lauded as the very embodiment of their ideology which they see as noble.

A major aspect of the game is capturing enemy soldiers you encounter and recruiting them to join your military nation. They provide you with in-game bonuses and when you return to your base, the characters you have recruited are around and interact with you. They have names and hobbies and hopes and dreams.

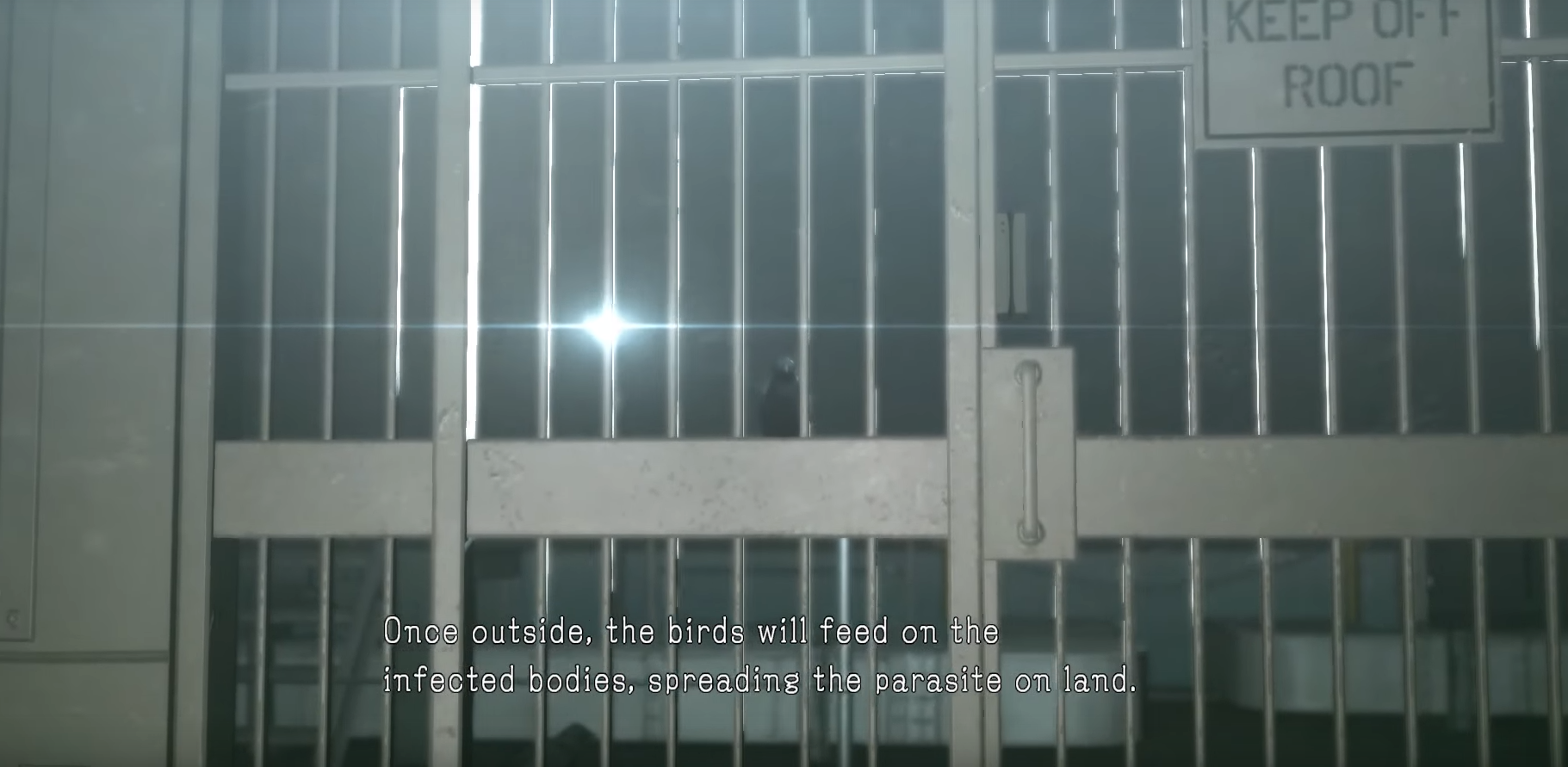

A key aspect of Metal Gear Solid V’s story revolves around a lethal vocal chord parasite that has become weaponized in a genocidal plot to eliminate certain languages from the planet. It is invisible, it is lethal and it has some kind of rudimentary intelligence. The parasite can learn a language and then go on to exclusively inhabit and kill its speakers.

When episode 43, titled “Shining Lights, Even in Death” is unlocked, near the very end of the game, you are called back to your home base. The vocal chord parasite has evolved immunity to the vaccine you previously developed to prevent its infection and there's been an outbreak on your isolated quarantine platform. You, in a gesture of leadership, enter the sealed off area alone in order to investigate.

The level itself is framed as horror. Screaming people, bloody trails, the occasional begging for help. Emergency lights illuminate the halls in an eerie fashion as you look for a person that might hold the key to identifying the infected. When you finally reach the soldier in question, it’s already apparent what lays ahead of you. He dies and you obtain specially engineered goggles that can detect the parasite in people’s throats. Then the screaming starts.