Sanity, Insanity and THE BABADOOK

What is worse: sanity or insanity? The question is at the centre of supernatural horror, and while the answer seems obvious from the experience of a reader (likely sane), things aren't so clean cut in the realm of lucid nightmares. Put yourself in the shaking boots of Amelia, the tortured mother from The Babadook, for instance, and then ask yourself which mental paradigm you would prefer.

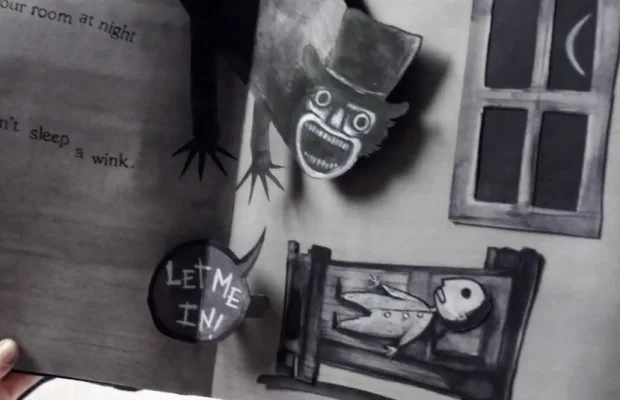

Aided by the unreliable narrator device that is typical of horror genre fiction, supernatural elements in stories like The Babadook thrive on the balance between the opposing worldviews of unbridled imagination and a strange reality. Throughout that film, the audience is given numerous hints that Amelia’s experience with the titular evil entity is simply a figment of her imagination born of insomnia, trauma and the stress of having a difficult child who builds weapons as a hobby. Stuck in her point of view, however, we are shown the Babadook as it appears to her: an increasingly real threat to the life of her son.

As viewers of Amelia’s struggle we are given two options on how to explain the film’s conflict. Is Amelia sane or insane, and which is worse? If she is insane - and the film’s ending is certainly open enough to suggest that she is being tortured by her mind - then the struggle exists solely within her home. The stakes are still very high, since an expressionist reading of the film forces you to accept that Amelia is trying to stop herself from a powerful urge to murder her son, but they are isolated. The same can’t be said if we accept a literal reading of the events.

If Amelia is perfectly sane in The Babadook, then she is perhaps worse off. The laws of our universe as we know them do not accommodate spectral, pop-up book enthusiasts who can manipulate reality and possess single mothers. The world proposed by a literal reading of The Babadook is near unthinkable. It is one in which we are wrong about everything and no one is safe. It is a reality that looks exactly like insanity.

In volume three of his Horror of Philosophy series, Tentacles Longer Than Night, Eugene Thacker says that it is the space between the definitive answers of sanity and insanity - a state which he terms fantasy - that horror thrives. Lovecraft and Poe, whose works make up the bulk of Thacker’s analysis, were masters of this balance. The author points to the introduction of Poe’s The Black Cat and Lovecraft’s The Shadow Out Of Time as pinnacle examples of this trope. Each story begins after the subsequently described events take place and the narrators specifically tell their readers that, given the unlikeliness of their recountings, it is quite possible they are insane.

In stories that evoke the question of a sane narrator, regardless of the medium, the question of reality is integral to the stakes and a key ingredient in the horror. It is the mark of a master, I think, when done properly and left unresolved. Either side – clear minded or off the rocker – provides an anchor from which an audience can navigate the supernatural events of a given tale. When those anchors are taken away, like they are in The Babadook, we are left to drift in the terrifying moments that make up the present. Here in the sea of uncertainty, where we live daily life, we can access something more terrifying than an unmapped reality or a broken brain: we face the human frailty contained in the thought that an explanation can’t save us from our present circumstances.